Why Storywork? Why Place-Responsive?

As a general term, storywork is about working with stories to make sense of people's lived experience, to interpret events, and to understand connections between contexts, for example between people, place, land, and language. I have provided more justification for the use of storywork by teachers, especially in response to place, on the Storywork homepage. To be place-responsive is about allowing for reciprocity in our relations with each other, the places we inhabit, and the more-than-human world. Place-responsiveness sees land as teacher, and, perhaps, points towards a regenerative way of doing education.

Lens -- Take Me Outside: https://takemeoutside.ca. "Take Me Outside is a non-profit organization committed to raising awareness and facilitating action on nature connection and outdoor learning in schools across Canada. We believe in a future in which spending time outside playing, exploring and learning is a regular and significant part of every learner’s day. We work collaboratively with other organizations, school boards and individuals to encourage children and youth to spend more time outside through various projects and initiatives."

Lens -- Education Outside the Classroom (EOTC): This is a position statement from the Environmental Educators Provincial Specialist Association (EEPSA). http://eepsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/EEPSA-Position-Statement-on-Education-Outside-the-Classroom.pdf. "Our K-12 BC Curriculum encourages teaches to take classroom learning outdoors... As excitement continues to grow around this work, more teachers are venturing outdoors. The educational community would benefit from reduced barriers and strategic funding."

Lens -- Six Touchstones for Wild Pedagogies in Practice: https://wildpedagogies.com/6%20Touchstones. "These touchstones can become points of departure and places to return to. They stand as reminders of what we, as wild pedagogues, are trying to do. And they challenge us to continue the work. These touchstones are offered to all educators who are ready to expand their horizons, and are curious about the potential of wild pedagogies. They are meant to be read, responded to, and revised as part of an evolving, situated, and lived practice."

Lens -- Take Me Outside: https://takemeoutside.ca. "Take Me Outside is a non-profit organization committed to raising awareness and facilitating action on nature connection and outdoor learning in schools across Canada. We believe in a future in which spending time outside playing, exploring and learning is a regular and significant part of every learner’s day. We work collaboratively with other organizations, school boards and individuals to encourage children and youth to spend more time outside through various projects and initiatives."

Lens -- Education Outside the Classroom (EOTC): This is a position statement from the Environmental Educators Provincial Specialist Association (EEPSA). http://eepsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/EEPSA-Position-Statement-on-Education-Outside-the-Classroom.pdf. "Our K-12 BC Curriculum encourages teaches to take classroom learning outdoors... As excitement continues to grow around this work, more teachers are venturing outdoors. The educational community would benefit from reduced barriers and strategic funding."

Lens -- Six Touchstones for Wild Pedagogies in Practice: https://wildpedagogies.com/6%20Touchstones. "These touchstones can become points of departure and places to return to. They stand as reminders of what we, as wild pedagogues, are trying to do. And they challenge us to continue the work. These touchstones are offered to all educators who are ready to expand their horizons, and are curious about the potential of wild pedagogies. They are meant to be read, responded to, and revised as part of an evolving, situated, and lived practice."

Overall Strategy foe Place-Responsive Stonework

Experiences in nature, outdoor learning activities, land-based learning, exploration of cultural and physical landscapes, bringing nature into the classroom -- these can be one-off events that are intended to tie into some curriculum or established learning in the classroom, of they can simply stand alone as a way of understanding and responding to place. However, over time it is possible to bring a sense of purpose and continuity to an place-responsive program, and transition from outdoor activities being a novelty or break from routine and become a core way of being in the world as teachers and students. For example, a Grade 7 teacher may want to try activities like Soundwalks, PhotoStories, or Narrative Fossicking to compliment what is happening in a Science unit. After a few excursions, they notice that some students really like one strategy over the other, and provide feedback that the activity was useful. The teacher might then plan a place-responsive Social Studies unit that starts with the idea that students will each use two of the activities as the basis for their inquiry, with additional choices including RePhotography, and Community Interviews. This is a way of differentiating that is mostly on the students, and as their inquires come together, will provide a rich (if eccentric) account of the focus topic. If done in groups (e.g. 6 broad inquiry topics for a class, groups of 4), it provides a way for teachers to assess students individually, as they are each applying unique strategies to add to their group account.

Supplies for Place-Responsive Storywork

|

Each of the place-responsive ventures mentioned on this site contains a list of suggested supplies, but it is a great idea to build up a bin of useful items that you can use each time you take a class outdoors, with variations depending on the context, climate, or curriculum. Clipboards or hard rectangles of plastic or pressboard for any kind of writing or drawing, Duksbak or Rite-in-the-rain paper for wet outings, and so on. One of my colleagues heads out with garbage bags that can be used to sit on or as makeshift raincoats if the clouds roll in unexpectedly.

Another colleague always has a bundle of sitting mats ready to go. He started calling them butt pads, but got negative reviews, so now he calls them sit-pads. They are made by cutting inexpensive sleeping pads (CanTire, $12) into four sit-pads, and tied up for easy transport -- two bundles of 15 (which makes a class set) can be carried easily by a couple of students. These are perfect for building an instant outdoor classroom, provide a bit of comfort on cold, damp ground, or making the top of a log more agreeable, and protect students' clothes from getting full of dirt, pitch, or ants. Or at least you'll see the ants coming a little easier. |

Stories as Learning Resources in Social Studies

WRITTEN ACCOUNTS

Consider the use of short stories, memoirs, passages from books or other recollections (primary or secondary), biographies, ethnographies, and so on as learning objects. These can and should compete with textbooks.

AUDIO ACCOUNTS

Consider the use of recorded (or even live) interviews, podcasts, audio stories, archived radio shows, and so on as learning objects. Although use of transcriptions can be useful, they joy of an audio account is simply to hear a personable account or story and use these to inform judgements, offer perspective, or provoke questions and discussion.

VIDEO ACCOUNTS

Consider the use of video accounts, e.g. recorded testimony or interviews, portions of documentaries, vlogs, and so on as learning objects. Look for storytelling from expert witnesses – informed perspectives that shed light on topics under study.

GRAPHIC NOVELS

Many graphic novels deal with events and phenomenon relevant to Social Studies. Maus by Art Spiegelman comes to mind immediately. However, search for others (with the help of your school's teacher-librarian if you have one) well in advance of your unit of study that fit a theme or topic your students will be exploring. A great example of a work that uses graphics, and no words, to tell stories of immigration, is The Arrival by Shaun Tan. Use these often enough, and students will want to tell their stories and express their learning using this format. If you find that some graphic novels are useful year after year, have your school's teacher-librarian order a set.

Consider the use of short stories, memoirs, passages from books or other recollections (primary or secondary), biographies, ethnographies, and so on as learning objects. These can and should compete with textbooks.

AUDIO ACCOUNTS

Consider the use of recorded (or even live) interviews, podcasts, audio stories, archived radio shows, and so on as learning objects. Although use of transcriptions can be useful, they joy of an audio account is simply to hear a personable account or story and use these to inform judgements, offer perspective, or provoke questions and discussion.

VIDEO ACCOUNTS

Consider the use of video accounts, e.g. recorded testimony or interviews, portions of documentaries, vlogs, and so on as learning objects. Look for storytelling from expert witnesses – informed perspectives that shed light on topics under study.

GRAPHIC NOVELS

Many graphic novels deal with events and phenomenon relevant to Social Studies. Maus by Art Spiegelman comes to mind immediately. However, search for others (with the help of your school's teacher-librarian if you have one) well in advance of your unit of study that fit a theme or topic your students will be exploring. A great example of a work that uses graphics, and no words, to tell stories of immigration, is The Arrival by Shaun Tan. Use these often enough, and students will want to tell their stories and express their learning using this format. If you find that some graphic novels are useful year after year, have your school's teacher-librarian order a set.

Presentation Notes

2023 Outdoor Learning Conference: Responding to Place Through Storywork and Experiential Learning: Workshop Handout | Conference Website

2022 Canadian Geographic Education Summer Conference: Responding to Place to Storywork -- slides

2022 Canadian Geographic Education Summer Conference: Responding to Place to Storywork -- slides

Assessment using oral accounts and/or story formats

STUDENT INTERVIEWS

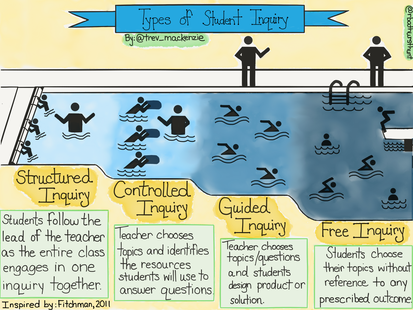

One of the simplest ways to conduct assessment in Social Studies is to provide students with opportunities to share an oral account of what they have learned. Similar to the kinds of inquiry described in Trevor Mackenzie's graphic (illustrated by Rebecca Bushby), student interviews could take a variety of forms. Some suggestions:

These examples above all involve preparation and a formal interview. Regardless of the necessity of including facts, addressing prompts, and so on, they use of storytelling techniques is what makes this format creative and critical. As the student builds narrative account, a story of what they know, they are committing their identity to their learning, owning perspectives, defending choices, relate personal experience, and showing personal responsibility (not to mention personality) for learning intentions -- an authentic perspective rooted in learned material, but not simply regurgitating what they have read or absorbed. The possibilities of story are only realized if the interviewer (i.e. the teacher) uses questioning techniques (e.g. use of the prompts, clarifying questions, etc.) to motivate the interviewee to expand on what they are saying, to fill in gaps, to discuss forks in their story, or simply ensure that the student knows what they are talking about. The other factor that will liberate this approach is limited use of notes and props. The whole point of the preparation and format is that students are able to talk about what they know, answer questions, discuss, fill in the details, or make appropriate connections to other aspects of study or learning intentions. An interview is not a recitation of a prepared script, it is a story unfolding in real time, with some give and take between the interviewer and interviewed, and always the possibility that it will choose its own direction. The interview is also a marvellous opportunity for the teacher to offer appreciative and/or critical feedback, and to differentiate assessment based on the identity and learning trajectory of the student.

Interviews do not need to be formal. With an agreed-upon amount of time to prepare (e.g. could be zero – impromptu, or could be fifteen minutes to gather thoughts and review notes, students can simply be asked to talk about what know about a particular topic, question, event, phenomenon, or lived experience. The teacher will learn a great deal about what students know and understand by this means, and is particularly useful in cases where the written work of students does not suggest originality or critical thought. Informal interviews might not be used in the same way as a formal interview to generate marks or place student progress on scale, but they can inform, confirm, challenge, or possibly replace other assessment measures. For example, a student completes an in-class assessment on the causes of WWI. In reviewing the student's work, the teacher notices that the information provided is inadequate, has gaps, does not show understanding, or looks like something copied or made up. it would not receive a passing grade, or provide evidence of progress towards meeting expectations. Rather than ask this student to re-do the assessment again, an alternative might be to show the student where their work had gaps, suggest what they should review in order to establish a base understanding. After an agree-upon length of time, the student is interviewed about the content or questions that were the focus of the original assessment. If the teacher is satisfied with the student's understanding, the student could receive a passing grade for the assessment, or be scaled as meeting expectations, and so on. This may actually save time and may respect the integrity of an assessment (e.g. repeating a bespoke assessment may defeat the purpose). The interview also makes it very clear whether the student's understanding is emerging, developing, proficient, etc. – often (bit not always) much clearer than a written response.

One of the simplest ways to conduct assessment in Social Studies is to provide students with opportunities to share an oral account of what they have learned. Similar to the kinds of inquiry described in Trevor Mackenzie's graphic (illustrated by Rebecca Bushby), student interviews could take a variety of forms. Some suggestions:

- Structured interview: the teacher and students work through one or more topics together, establishing big ideas, themes, evidence, exemplars, application of competencies, and so on. This could be done as a summary activity after a period of study such as a lecture or slideshow with notes, a documentary study, an inquiry project, even worksheets and textbook questions. Prompts should relate to an equivalent outcome or learning intention that would normally be assessed on a test, paper, or assignment: Why should Canadians care about what is happening in the Ukraine? What caused WWI? Why are some statues of historical figures being removed in Canada? Once there is a "case" that the students understand (e.g. they can adequately summarize the key notions of a learning intention), the teacher and students co-construct an account that satisfies the teachers' criteria (e.g. establishes historical or geographical significance, involves use of diverse primary sources, etc.) and includes key points to mention in an interview. The students are then given opportunities to interview each other to assess (self or otherwise) their ability to express what they have learned in an oral format.

- Controlled Interview: the students are provided with specific prompts related to defined (already learned) class topics that they should respond to in their oral account, as well as a list of key indicators, evidence, or criteria that students should address. Each prompt could come with criteria; for example, 5 Ws, explanation of cause & effect, two or more perspectives, and so on. The students are also given a template or guide for preparing an oral account, or a story of learning, and some time to prepare their notes or organize their account. Interviews could take place in group circle with the interview (this works well if there is some variety in the prompts), or one on one as they are ready (this works well if the class is working on something else that does not require direct instruction or involvement of the teacher). The interviews could also be conducted with a different teacher. The prompts are used to drive the interview – to move it along as needed.

- Guided Interview: the students are reminded of the general topics from a period of study, and given some time to consider some possible prompts provided by the teacher. The students settle on an appropriate prompt and design an oral account or story of learning and highlights what they understand about the topic. The teacher may also provide specific criteria for responses (e.g. 5 Ws, considerations of continuity and change or ethical dimensions, etc.) or the students may negotiate with the teacher about what kinds of things they wish to include in their oral account. Interviews could take place in groups or one-on-one, and could also be conducted with a different teacher. The prompts can be used to move the interview along, or may be changed up to provide clarity for the interviewer and opportunities to express understanding by the interviewee.

- Free Interview: the students may select both the topics from a course of study and develop appropriate prompts and criteria that probe the topics as they design an oral account. Free does not mean ad-lib, so there should be some check-in with the teacher and expectation of prepared material. Interviews could take place in groups or one-on-one, and could also be conducted with a different teacher. The student or the teacher can pause during an interview to make sure the other is satisfied in terms or clarity, depth, and so on.

These examples above all involve preparation and a formal interview. Regardless of the necessity of including facts, addressing prompts, and so on, they use of storytelling techniques is what makes this format creative and critical. As the student builds narrative account, a story of what they know, they are committing their identity to their learning, owning perspectives, defending choices, relate personal experience, and showing personal responsibility (not to mention personality) for learning intentions -- an authentic perspective rooted in learned material, but not simply regurgitating what they have read or absorbed. The possibilities of story are only realized if the interviewer (i.e. the teacher) uses questioning techniques (e.g. use of the prompts, clarifying questions, etc.) to motivate the interviewee to expand on what they are saying, to fill in gaps, to discuss forks in their story, or simply ensure that the student knows what they are talking about. The other factor that will liberate this approach is limited use of notes and props. The whole point of the preparation and format is that students are able to talk about what they know, answer questions, discuss, fill in the details, or make appropriate connections to other aspects of study or learning intentions. An interview is not a recitation of a prepared script, it is a story unfolding in real time, with some give and take between the interviewer and interviewed, and always the possibility that it will choose its own direction. The interview is also a marvellous opportunity for the teacher to offer appreciative and/or critical feedback, and to differentiate assessment based on the identity and learning trajectory of the student.

Interviews do not need to be formal. With an agreed-upon amount of time to prepare (e.g. could be zero – impromptu, or could be fifteen minutes to gather thoughts and review notes, students can simply be asked to talk about what know about a particular topic, question, event, phenomenon, or lived experience. The teacher will learn a great deal about what students know and understand by this means, and is particularly useful in cases where the written work of students does not suggest originality or critical thought. Informal interviews might not be used in the same way as a formal interview to generate marks or place student progress on scale, but they can inform, confirm, challenge, or possibly replace other assessment measures. For example, a student completes an in-class assessment on the causes of WWI. In reviewing the student's work, the teacher notices that the information provided is inadequate, has gaps, does not show understanding, or looks like something copied or made up. it would not receive a passing grade, or provide evidence of progress towards meeting expectations. Rather than ask this student to re-do the assessment again, an alternative might be to show the student where their work had gaps, suggest what they should review in order to establish a base understanding. After an agree-upon length of time, the student is interviewed about the content or questions that were the focus of the original assessment. If the teacher is satisfied with the student's understanding, the student could receive a passing grade for the assessment, or be scaled as meeting expectations, and so on. This may actually save time and may respect the integrity of an assessment (e.g. repeating a bespoke assessment may defeat the purpose). The interview also makes it very clear whether the student's understanding is emerging, developing, proficient, etc. – often (bit not always) much clearer than a written response.

Historical and Geographical Thinking Concepts

Historical and Geographical Thinking Concepts are at the heart of the revised Social Studies curriculum in British Columbia. They are a good fit for Place-Responsive Storywork, and can be used as organizing concepts or as end-goals. Here are some examples of research questions that could be used to explore the concepts:

- Establishing Significance: How does a personal story or a one-time experience connect with larger events of a time period or location? Can evidence of historically or geographically significant events be seen in a local landscape?

- Using Source Evidence: Can primary sources from various time period (e.g. maps, photos, documents) be used to build an account of place, or provide factual details (non-fiction!!) for a particular event under consideration of story being told? Can the evidence be trusted to tell an accurate story? What part of the story? What evidence would you need to make the story accurate or whole? Can these needs be met by collecting field evidence?

- Identifying Continuity and Change: What patterns of continuity (things staying the same) can be found within a community? How do we know this? How have individual places and ecosystems changed over time? What has remained the same, or shown remarkable resilience to change?

- Analyzing Cause and Consequence: Why did Indigenous nations end up living where they did? What about settlers? What adaptation to place have been made, and in response to what underlying causes? Why did local people end up in the occupations they currently have? What accounts for the way a place has been altered, or a community settled, or a region taking on a cultural identity? What are the main causes of landscape change in your area, and are these changes sustainable?

- Perspective Taking: How can the attitudes, values, beliefs, and perspectives of past residents be characterized? What was their sense or experience of place? Are these consistent with other perspectives at the times? What other perspectives are worth considering related to the time period and events? You can do the same for current residents.

- Understanding Ethical Dimensions: What kinds of difficult choices were faced by people in this area? Any comments to make about attitudes towards minorities, the environment, governments, war, and so on? Any experiences of colonization in this area that stand out? Do any of the issues or challenges resemble ethical issues seen in the the larger world, or are they unique to this area?