Academic and Professional Writing Samples

From book "Thinking it Through" a Social Studies Sourcebook

Introduction to the Sourcebook (used as a reading in UNBC EDUC 460) pdf

Context: Critical Thinking exercises for BC Social Studies 9 students. Excerpt (p. xii-xiii)

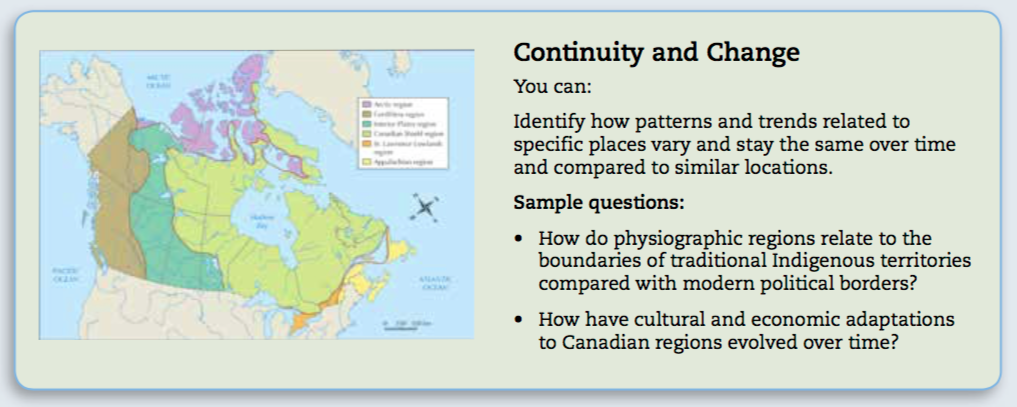

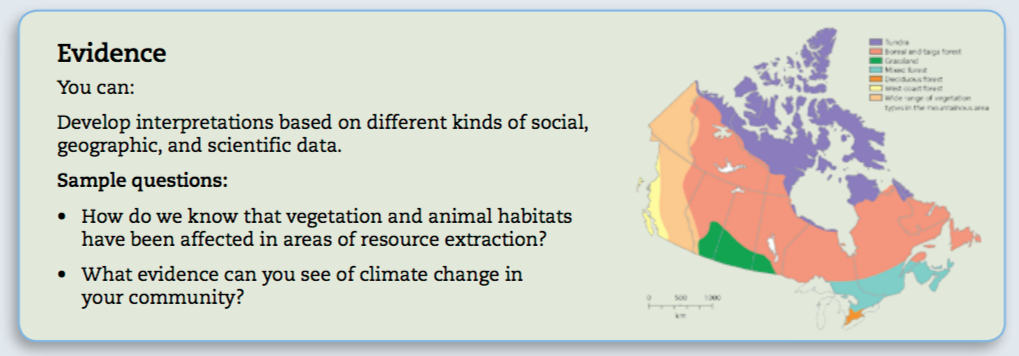

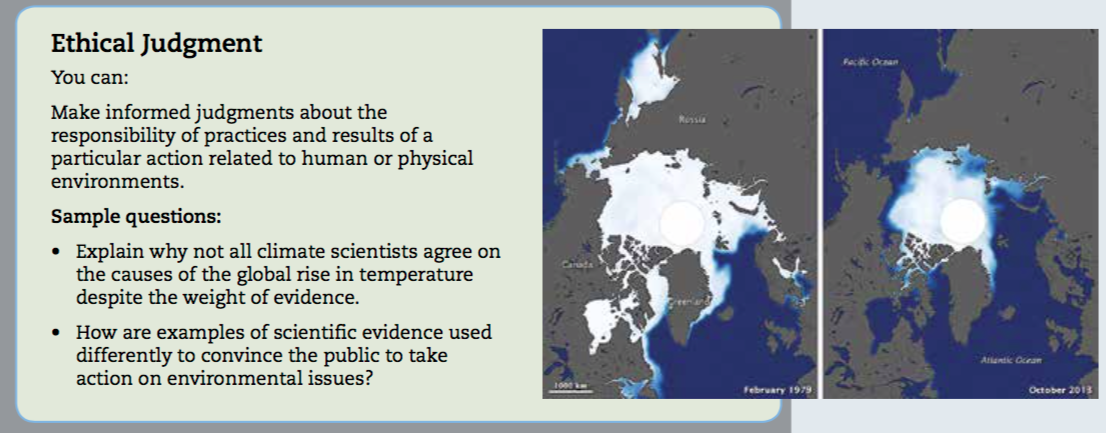

Using Geographic Thinking

Similar to the historical thinking concepts, these concepts will help you examine different perspectives, weigh evidence, explain causes and consequences, and make critical judgments. They will help you understand the role and characteristics of place and location in all aspects of human society. You can use the concepts to help respond to the sources and questions in the Sourcebook, or you can work from the other direction and use the Sourcebook to help you understand the concepts.

Context: Critical Thinking exercises for BC Social Studies 9 students. Excerpt (p. xii-xiii)

Using Geographic Thinking

Similar to the historical thinking concepts, these concepts will help you examine different perspectives, weigh evidence, explain causes and consequences, and make critical judgments. They will help you understand the role and characteristics of place and location in all aspects of human society. You can use the concepts to help respond to the sources and questions in the Sourcebook, or you can work from the other direction and use the Sourcebook to help you understand the concepts.

From Distance Ed Course Project: Sustainable Resources 12 - Forestry

Treeplanting: A Prince George Case Study. 2011 (pdf)

Excerpt (p. 3): The 1980s and early 1990s were boom years for treeplanting, with many contractor companies starting up and seeking youth willing to work hard in rough conditions. This appealed to many college students, migrant workers (from other provinces and other countries), and even a few “back-to-the-landers” who saw treeplanting as a chance to experiment with intentional community (like hippies in the 1960s counterculture, but in the 1980s). In the 1970s and throughout most of the 1980s, treeplanting camps were basic and had few safety requirements. Planters often took turns cooking, hauled water from streams, and used their own vehicles and equipment. New Worker’s Compensation Board mandates in 1988 meant that camps soon became safer, more bear-aware, had hot showers, outhouses, filtered water, and paid food service (rustic catering that usually included a camp cook and helper). Treeplanting companies (who had successfully bid on the contract to plant a specific area) supplied most of the necessary equipment, usually including trucks, vans, crummies (from the word crew, basically a truck with a deck and benches in the back for the crew) and rolligons (all-terrain transport vehicles), quads, or cook buses. Keeping all that equipment in good order, and complying with worker safety regulations was expensive and cut into profits, so stories of “cutting corners” and passing on costs to treeplanters were very common. It did not take long for contractors and silviculture contractors to gain positive and negative reputations, but a steady supply of contracts and willing labour allowed unscrupulous companies to survive.

Excerpt (p. 3): The 1980s and early 1990s were boom years for treeplanting, with many contractor companies starting up and seeking youth willing to work hard in rough conditions. This appealed to many college students, migrant workers (from other provinces and other countries), and even a few “back-to-the-landers” who saw treeplanting as a chance to experiment with intentional community (like hippies in the 1960s counterculture, but in the 1980s). In the 1970s and throughout most of the 1980s, treeplanting camps were basic and had few safety requirements. Planters often took turns cooking, hauled water from streams, and used their own vehicles and equipment. New Worker’s Compensation Board mandates in 1988 meant that camps soon became safer, more bear-aware, had hot showers, outhouses, filtered water, and paid food service (rustic catering that usually included a camp cook and helper). Treeplanting companies (who had successfully bid on the contract to plant a specific area) supplied most of the necessary equipment, usually including trucks, vans, crummies (from the word crew, basically a truck with a deck and benches in the back for the crew) and rolligons (all-terrain transport vehicles), quads, or cook buses. Keeping all that equipment in good order, and complying with worker safety regulations was expensive and cut into profits, so stories of “cutting corners” and passing on costs to treeplanters were very common. It did not take long for contractors and silviculture contractors to gain positive and negative reputations, but a steady supply of contracts and willing labour allowed unscrupulous companies to survive.

From my Master of Education 2002-2004

Natural Resource Management – UNBC Continuing Education – Program Evaluation, 2004 (co-authored, pdf)

Excerpt (p. 10-11):

EVALUATION OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of this formative evaluation was to assess the strengths and limitations of the Continuing Education Natural Resource Management program at UNBC and to develop recommendations for improvement (refer to Appendix B – Letter of Permission). In order to attain this objective a Management-Oriented evaluation approach was initiated. Under this approach the evaluators strived to identify recommendations that could be used to mitigate the constraints and enhance the benefits of the program. This evaluation focused specifically on the identification of client needs and barriers to program success. In order to meet this objective under this model of evaluation, the evaluators examined a variety of program characteristics and research questions involving multiple stakeholders (refer to Appendix C – Research Questions used to Address the Evaluation Objectives).

METHODOLOGY AND INSTRUMENTATION

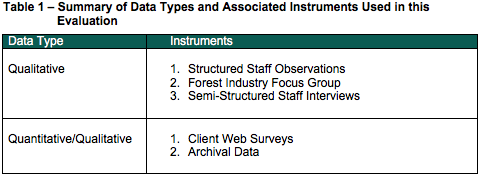

The evaluators systematically chose each method of analysis in order to meet the objectives of this evaluation. Each method had a number of strengths and a number of associated biases and sources of error; therefore, by using a variety of instruments with multiple stakeholders, the likelihood of corruption and distortion was decreased and the evaluation was strengthened. For this evaluation both qualitative and quantitative data were collected (Table 1). Using both types of data for interpretation, the evaluators were able to increase the overall validity and reliability of the evaluation.

Excerpt (p. 10-11):

EVALUATION OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of this formative evaluation was to assess the strengths and limitations of the Continuing Education Natural Resource Management program at UNBC and to develop recommendations for improvement (refer to Appendix B – Letter of Permission). In order to attain this objective a Management-Oriented evaluation approach was initiated. Under this approach the evaluators strived to identify recommendations that could be used to mitigate the constraints and enhance the benefits of the program. This evaluation focused specifically on the identification of client needs and barriers to program success. In order to meet this objective under this model of evaluation, the evaluators examined a variety of program characteristics and research questions involving multiple stakeholders (refer to Appendix C – Research Questions used to Address the Evaluation Objectives).

METHODOLOGY AND INSTRUMENTATION

The evaluators systematically chose each method of analysis in order to meet the objectives of this evaluation. Each method had a number of strengths and a number of associated biases and sources of error; therefore, by using a variety of instruments with multiple stakeholders, the likelihood of corruption and distortion was decreased and the evaluation was strengthened. For this evaluation both qualitative and quantitative data were collected (Table 1). Using both types of data for interpretation, the evaluators were able to increase the overall validity and reliability of the evaluation.

Policy and Identity: The Ecology of Self and the Negotiation of Interests in an Organization, 2003 (pdf)

Excerpt (p. 10-11): The ecological metaphor, used as a model for guiding a policy process, can create an inspirational vision, mobilize commitment, intensity, and energy, build uniqueness while allowing diversity, and foster social cohesion (Illes, 1999, p. 6). These possibilities are all fertile ground for the expression of identity (the alternative being repression), so while ecosystem view focuses attention on the character of the policy players, a deeper application of the metaphor has the potential for the transformation of identity. This, of course, depends on the amount one is willing to show of oneself in the policy process, but as people involve themselves with important issues, at least some part of their identity is at stake as they ‘find their niche.’ The risk of experimenting with transformative metaphors is that the policy process can change to the extent that the identity one has revealed can be threatened when the players must shift their paradigms to adapt. bell hooks describes a similar phenomenon in discussing an effort to transform an educational institution to reflect a multicultural perspective (hooks, 1994, p. 36).

Excerpt (p. 10-11): The ecological metaphor, used as a model for guiding a policy process, can create an inspirational vision, mobilize commitment, intensity, and energy, build uniqueness while allowing diversity, and foster social cohesion (Illes, 1999, p. 6). These possibilities are all fertile ground for the expression of identity (the alternative being repression), so while ecosystem view focuses attention on the character of the policy players, a deeper application of the metaphor has the potential for the transformation of identity. This, of course, depends on the amount one is willing to show of oneself in the policy process, but as people involve themselves with important issues, at least some part of their identity is at stake as they ‘find their niche.’ The risk of experimenting with transformative metaphors is that the policy process can change to the extent that the identity one has revealed can be threatened when the players must shift their paradigms to adapt. bell hooks describes a similar phenomenon in discussing an effort to transform an educational institution to reflect a multicultural perspective (hooks, 1994, p. 36).

The Treeplanter Camp and Crew: An Organizational Analysis, 2003 (pdf)

Excerpt 1 (p. 8): The idea of treeplanting as a culture, or the emulation of a culture, is perhaps the most appropriate metaphor if the organization is viewed from the perspective of the individual camp and crew. At a different scale, the dynamics have changed: the silvicultural company is (or has become) much more than a collection of crews; it is a corporate entity that respects the cultures developed by crews (e.g. turns a blind eye to drug use, places photos of camp life on their website), but places its focus on profit. If the crew is a culture, then it operates on both sides of the political spectrum: “we’re motivated by competition and camaraderie” (Shane Cooke, personal interview, March 26/03). The profit-motive and daily reminders about production (from the foreman) and quality (from the checker) speak to the entrepreneurial ethic of most crews. Planters are very much familiar with fines and bonuses, special fees, and incentives (Goerz, 1996, p. 104). But the crew culture is also a utopian endeavour, an exercise in interdependence that requires individuals to give up freedom for the sake of the social experiment.

Excerpt 2 (): In the male-dominated demographics of planting, all-female crews were rare and provided male planters with their own version of the Amazon fantasy. Mixed crews were more common, with women often performing stereotyped tasks when the daily planting was done (or on days off) such as assisting the cook, organizing the camp, and mending gear: “it’s like we created a new society where we hung on to all the values we thought we had left behind. We didn’t see through it, with all the bugs and sweat and trees” (Kate Cooke, personal interview, March 26/03). Roles learned in family settings were initially transferred to crew life, although crews that had months to bond created unique roles as their culture was negotiated by the demands of the job and the personalities of the planters. Female planters (comprising 25% of BC crews) have a higher drop-out rate in the first season, but the ones that last to the second season “compete” with the men for tallies and endurance. Beyond competition and expressions of sexuality are notions of transformation accompanying many of the testimonies offered by women on treeplanter websites and in print: "It’s strange to me that the many hardships I encountered have faded from my memory and when I reflect on my planting experience I do so with a smile. Treeplanting has left me a stronger woman, both physically and mentally, and I feel a sense of empowerment that has followed me out of the bush." (Katherine Barkley in Cyr, 1998, p.89)

Excerpt 1 (p. 8): The idea of treeplanting as a culture, or the emulation of a culture, is perhaps the most appropriate metaphor if the organization is viewed from the perspective of the individual camp and crew. At a different scale, the dynamics have changed: the silvicultural company is (or has become) much more than a collection of crews; it is a corporate entity that respects the cultures developed by crews (e.g. turns a blind eye to drug use, places photos of camp life on their website), but places its focus on profit. If the crew is a culture, then it operates on both sides of the political spectrum: “we’re motivated by competition and camaraderie” (Shane Cooke, personal interview, March 26/03). The profit-motive and daily reminders about production (from the foreman) and quality (from the checker) speak to the entrepreneurial ethic of most crews. Planters are very much familiar with fines and bonuses, special fees, and incentives (Goerz, 1996, p. 104). But the crew culture is also a utopian endeavour, an exercise in interdependence that requires individuals to give up freedom for the sake of the social experiment.

Excerpt 2 (): In the male-dominated demographics of planting, all-female crews were rare and provided male planters with their own version of the Amazon fantasy. Mixed crews were more common, with women often performing stereotyped tasks when the daily planting was done (or on days off) such as assisting the cook, organizing the camp, and mending gear: “it’s like we created a new society where we hung on to all the values we thought we had left behind. We didn’t see through it, with all the bugs and sweat and trees” (Kate Cooke, personal interview, March 26/03). Roles learned in family settings were initially transferred to crew life, although crews that had months to bond created unique roles as their culture was negotiated by the demands of the job and the personalities of the planters. Female planters (comprising 25% of BC crews) have a higher drop-out rate in the first season, but the ones that last to the second season “compete” with the men for tallies and endurance. Beyond competition and expressions of sexuality are notions of transformation accompanying many of the testimonies offered by women on treeplanter websites and in print: "It’s strange to me that the many hardships I encountered have faded from my memory and when I reflect on my planting experience I do so with a smile. Treeplanting has left me a stronger woman, both physically and mentally, and I feel a sense of empowerment that has followed me out of the bush." (Katherine Barkley in Cyr, 1998, p.89)