HERITAGE INQUIRY AND STORYWORK

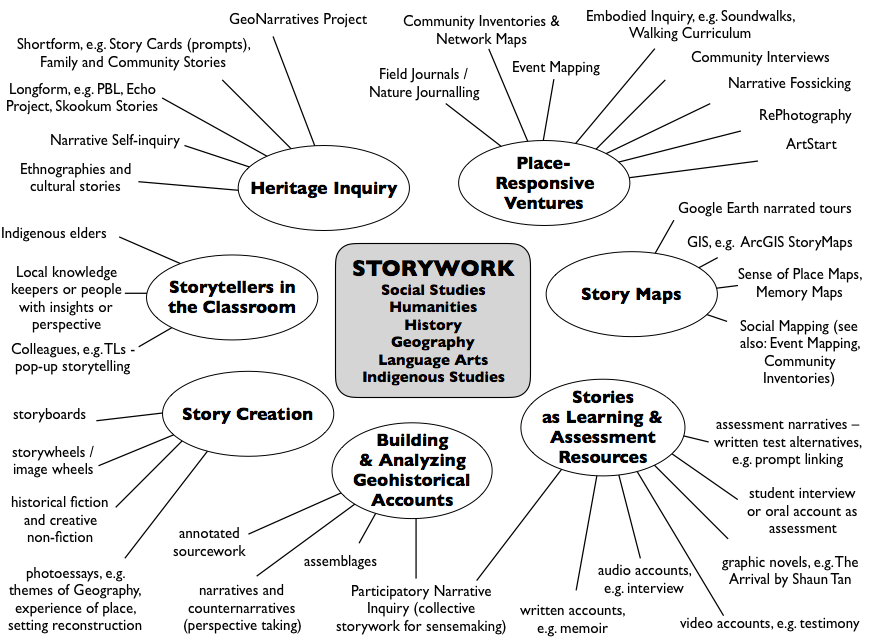

Many options exist for engaging Social Studies and Humanities students in storywork. Storywork is a pedagogical approach that extends the BC curricular competencies into the realm of identity, and provides an outlet for cross-curricular inqiury, Indigenous persectives, place-responsiveness, and alternative assessment.

What is Storywork?

As a general term, storywork is about working with stories to make sense of people's lived experience, to interpret events, and to understand connections between contexts, for example between people, place, land, and language.

Indigenous Storywork is the title of a book and the name of research and community engagement by Q’um Q’um Xiiem, Dr. Jo-ann Archibald, Professor Emeritus, UBC Faculty of Education. This kind of storywork relates to Indigenous pedagogies and use of stories for educating youth and others, helping them makes sense of lived experience, understanding historical and geographical contexts, and more. Indigenous Storywork is both a protocol for research and practice as well as a framework or way of viewing knowledge and experience.

Participatory Narrative Inquiry (PNI) is a methodology for working with stories to explore community identity, makes sense of experience and contexts, and make sense of problems or dynamics that exist in organizations or groups of people. It can also be used with students to practice sensemaking using their own stories as the basis of inquiry. An important contributor to the theory and practice of PNI is the American author and researcher Cynthia Kurtz.

Indigenous Storywork is the title of a book and the name of research and community engagement by Q’um Q’um Xiiem, Dr. Jo-ann Archibald, Professor Emeritus, UBC Faculty of Education. This kind of storywork relates to Indigenous pedagogies and use of stories for educating youth and others, helping them makes sense of lived experience, understanding historical and geographical contexts, and more. Indigenous Storywork is both a protocol for research and practice as well as a framework or way of viewing knowledge and experience.

Participatory Narrative Inquiry (PNI) is a methodology for working with stories to explore community identity, makes sense of experience and contexts, and make sense of problems or dynamics that exist in organizations or groups of people. It can also be used with students to practice sensemaking using their own stories as the basis of inquiry. An important contributor to the theory and practice of PNI is the American author and researcher Cynthia Kurtz.

Why is story important?

Consider these perspectives:

“The same stories heard over and over again become embdedded in one’s being, staying there until reflecion in one’s later years brings adult understandings and sometimes enables one to become a storyteller. Making meaning from a particular story can happen at various phases of human developments; the meaning may change over time. Stories, then, have a way of ‘living,’ of being perpetuated both by the listener/learner’s way of making meaning and by the storytellers, who have an important responsibility to tell stories in a particular way.” Jo-ann Archibald / Q’um Q’um Xiiem, Indigenous Storywork, p. 113

“The story and the storyteller both serve to connect the past with the future, one generation with the other, the land with the people and the people with the story.” Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, p. 146

“The truth about stories is that that’s all we are.” Thomas King, The Truth About Stories, p. 2

“When we talk about the concept of reconciliation, I think about some of the stories that I’ve heard in our culture and stories are important.... These stories are so important as theories but at the same time stories are important to oral cultures. So when we talk about stories, we talk about defining our environment and how we look at authorities that come from the land and how that land, when we talk about our relationship with the land, how we look at forgiveness and reconciliation is so important when we look at it historically.” Elder Reg Crowshoe, from testimony to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission

“She only nodded. “It’s all we are in the end. Our stories.” Richard Wagamese, Medicince Walk

“The same stories heard over and over again become embdedded in one’s being, staying there until reflecion in one’s later years brings adult understandings and sometimes enables one to become a storyteller. Making meaning from a particular story can happen at various phases of human developments; the meaning may change over time. Stories, then, have a way of ‘living,’ of being perpetuated both by the listener/learner’s way of making meaning and by the storytellers, who have an important responsibility to tell stories in a particular way.” Jo-ann Archibald / Q’um Q’um Xiiem, Indigenous Storywork, p. 113

“The story and the storyteller both serve to connect the past with the future, one generation with the other, the land with the people and the people with the story.” Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, p. 146

“The truth about stories is that that’s all we are.” Thomas King, The Truth About Stories, p. 2

“When we talk about the concept of reconciliation, I think about some of the stories that I’ve heard in our culture and stories are important.... These stories are so important as theories but at the same time stories are important to oral cultures. So when we talk about stories, we talk about defining our environment and how we look at authorities that come from the land and how that land, when we talk about our relationship with the land, how we look at forgiveness and reconciliation is so important when we look at it historically.” Elder Reg Crowshoe, from testimony to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission

“She only nodded. “It’s all we are in the end. Our stories.” Richard Wagamese, Medicince Walk