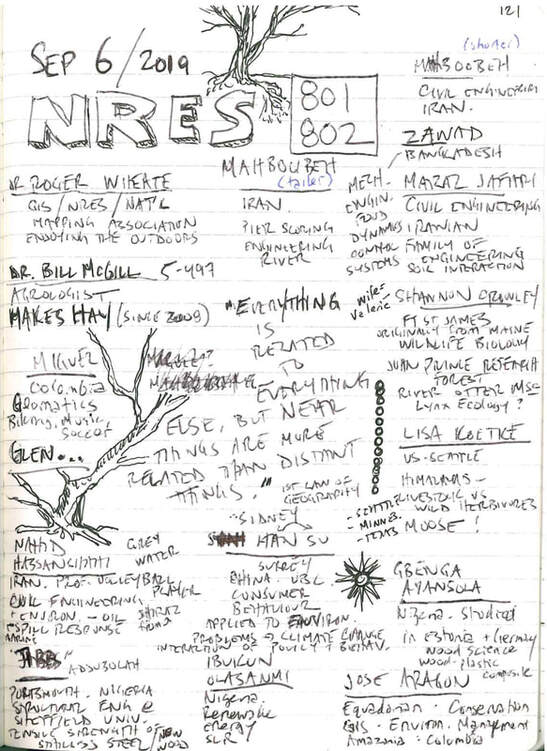

Day one with a new cohort, and there was some expected nervousness and excitement on the faces as they moved into the classroom. Not all would make it for the first class -- there were apparently some problems with travel -- but we would eventually become a group of fourteen. This reminded me of the party of 13 dwarves and one hobbit that set out for the Lonely Mountain in Tolkien's beloved story The Hobbit. I would not hazard a guess as to who is who in the group... not all the dwarves met with a happy fate. The fifteenth member of that party was of course the wizard Gandalf and we have our own wizard in the form of Dr. Bill McGill.

We are an international crew. I'm from Canada, a high school Social Studies teacher with some forays into other "Educational" work and some distant but memorable roots in forest ecology. Mahboubeh, Mahboobeh, Maral, and Nahid are all engineers and from Iran. Shannon and Lisa are both Americans by birth and connected to wildlife biology, but have travelled, lived, and studied in many places. Gbenga, Ajibola (Jibbs), and Ibukun are from Nigeria, with some detours, and are also engineers. Sidney is originally from China, and has a diverse research interests that I'm still not sure how to characterize. Jose is from Equador and is involved in environmental management. Miguel is from Colombia and is involved in geomatics. Zawad is from Bangladesh and completes our list of engineers. Dr. Roger Wheate is the Acting Chair of the NRES Grad Program and a frequent guest in our class; I suppose he is competition for the role of Gandalf. Dr. Bill McGill is an excellent fit for our group. I really appreciate the course design and emphasis on thought and discussion; this may not be everyone's cup of tea but I'll drink it any day. This ages me a bit, and Dr. McGill as well, but I must say this experience has reminded me of my undergrad days at UBC in the late 1980s and early 1990s, sitting in a classes and listening to sages, trying to keep up with powerful ideas and challenging questions. I knew we were in for a great adventure when Dr. McGill set up his juiciest questions with "let me torment you with this" or "let me harangue you with this."

NRES 801 and 802 have been fully integrated for our cohort. This means that we will examine issues in biophysical sciences and social sciences through similar lenses. For example, problem-solving in the biophysical sciences might relate to use of technology, whereas in the social sciences it might relate to policy development. For me, as someone squarely from the social sciences (even my approach to teaching physical geography to high school students centred on humanistic and human-environment adaptive perspectives), standing upright at the mirror of hard science is daunting. Do I belong here? Does my limited background in chemistry, physics, and mathematics make me look fat? (I am standing at a mirror, after all). Knowing that my colleagues, mostly engineers, are thinking the same thing about social sciences gives me pause to realize that this will be ok. As I'm understanding the unfolding syllabus, this program is not so much about diving into the sciences themselves but about examining critical issues related to these sciences, such as bias, ethics, methodological considerations, and interdisciplinarity. I'm finding that the biophysical research and social science research have a lot in common in terms of philosophic issues, but usually go in different directions when it comes to methodology and appeal to objectivity. On this last point I must add my amusement about how so many researchers in my field of Education (e.g. K-12 education, K-12 Social Studies education) are on a quest for some objective stance on best practice, for the most effective way to plan, teach, and assess. If we had as much respect for subjectivity and less trust in elaborate frameworks, perhaps we'd really get somewhere. This sounds like a preference for a form of dead reckoning over a more scientific approach to navigating education, and that is indeed what I mean. It is the stories we tell about where we are going in education that are proving most useful for new teachers, a series of course corrections with shifting goals, a sense of abandonment to the process and trust in our own values that guides our course and fills in the map. I feel as if I have not explained myself too well, here, so I hope to return to this topic. To me it is about exploring the dissonance between educational philosophy and practice that has become pronounced with the introduction of new K-12 curriculum in BC.

We are an international crew. I'm from Canada, a high school Social Studies teacher with some forays into other "Educational" work and some distant but memorable roots in forest ecology. Mahboubeh, Mahboobeh, Maral, and Nahid are all engineers and from Iran. Shannon and Lisa are both Americans by birth and connected to wildlife biology, but have travelled, lived, and studied in many places. Gbenga, Ajibola (Jibbs), and Ibukun are from Nigeria, with some detours, and are also engineers. Sidney is originally from China, and has a diverse research interests that I'm still not sure how to characterize. Jose is from Equador and is involved in environmental management. Miguel is from Colombia and is involved in geomatics. Zawad is from Bangladesh and completes our list of engineers. Dr. Roger Wheate is the Acting Chair of the NRES Grad Program and a frequent guest in our class; I suppose he is competition for the role of Gandalf. Dr. Bill McGill is an excellent fit for our group. I really appreciate the course design and emphasis on thought and discussion; this may not be everyone's cup of tea but I'll drink it any day. This ages me a bit, and Dr. McGill as well, but I must say this experience has reminded me of my undergrad days at UBC in the late 1980s and early 1990s, sitting in a classes and listening to sages, trying to keep up with powerful ideas and challenging questions. I knew we were in for a great adventure when Dr. McGill set up his juiciest questions with "let me torment you with this" or "let me harangue you with this."

NRES 801 and 802 have been fully integrated for our cohort. This means that we will examine issues in biophysical sciences and social sciences through similar lenses. For example, problem-solving in the biophysical sciences might relate to use of technology, whereas in the social sciences it might relate to policy development. For me, as someone squarely from the social sciences (even my approach to teaching physical geography to high school students centred on humanistic and human-environment adaptive perspectives), standing upright at the mirror of hard science is daunting. Do I belong here? Does my limited background in chemistry, physics, and mathematics make me look fat? (I am standing at a mirror, after all). Knowing that my colleagues, mostly engineers, are thinking the same thing about social sciences gives me pause to realize that this will be ok. As I'm understanding the unfolding syllabus, this program is not so much about diving into the sciences themselves but about examining critical issues related to these sciences, such as bias, ethics, methodological considerations, and interdisciplinarity. I'm finding that the biophysical research and social science research have a lot in common in terms of philosophic issues, but usually go in different directions when it comes to methodology and appeal to objectivity. On this last point I must add my amusement about how so many researchers in my field of Education (e.g. K-12 education, K-12 Social Studies education) are on a quest for some objective stance on best practice, for the most effective way to plan, teach, and assess. If we had as much respect for subjectivity and less trust in elaborate frameworks, perhaps we'd really get somewhere. This sounds like a preference for a form of dead reckoning over a more scientific approach to navigating education, and that is indeed what I mean. It is the stories we tell about where we are going in education that are proving most useful for new teachers, a series of course corrections with shifting goals, a sense of abandonment to the process and trust in our own values that guides our course and fills in the map. I feel as if I have not explained myself too well, here, so I hope to return to this topic. To me it is about exploring the dissonance between educational philosophy and practice that has become pronounced with the introduction of new K-12 curriculum in BC.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed