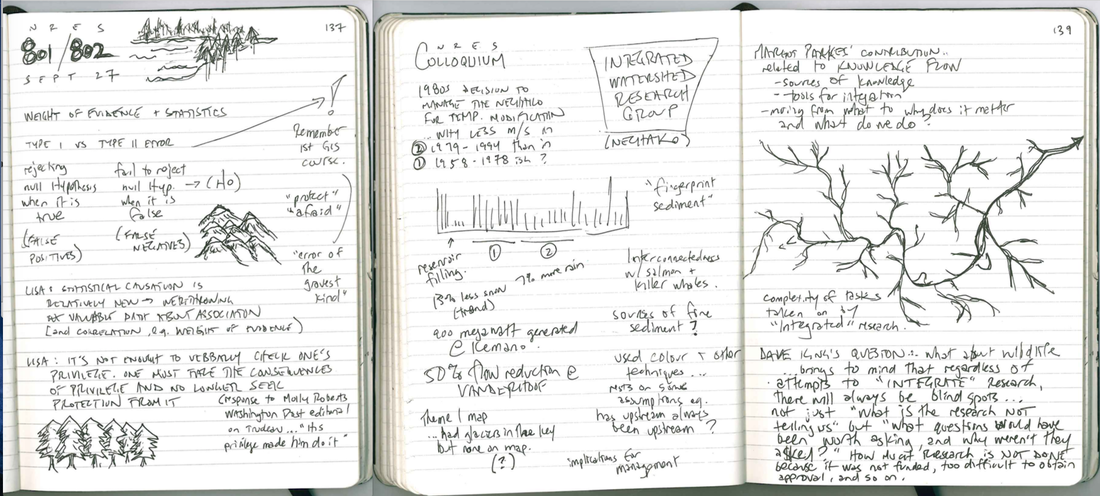

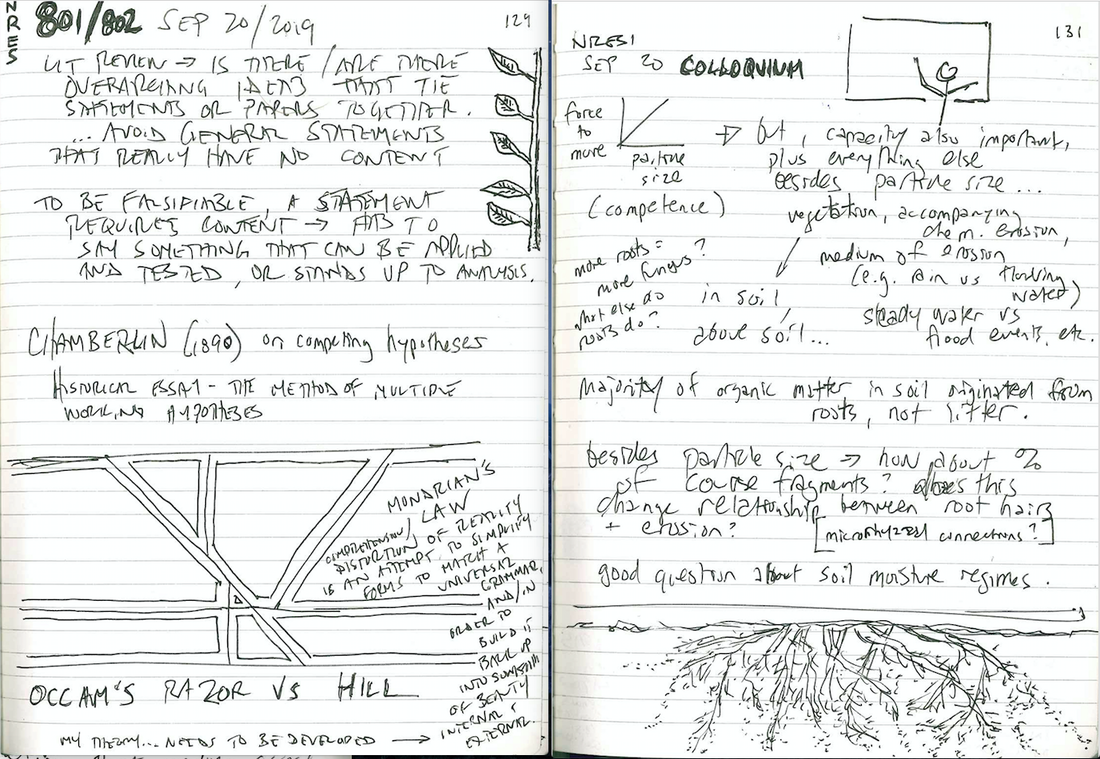

This class was mostly a chance to get organized for our group project, but we did have time to consider issues related to evidence and causation. It also featured a memorable quote from our colleague Lisa who deftly summed up a key insight in the ongoing consideration of equity in our society: "It is not enough to verbally check one's privilege. One must face the consequences of privilege and no longer seek protection from it." The debate in literature and the discussion in class on "weight of evidence" vs statistical tests for causation was interesting for me. I'd like to consider how both of these approaches have suffered in the field of K-12 educational policy.

Whether on the local scale, in setting school district priorities, school-based growth plans, and even personal teacher plans for improving their practice, or at the provincial scale, in designing and implementing curriculum and related educational policy, there is a constant return to "what is the evidence telling us." This seems like a healthy approach, but runs into trouble when there is disagreement on what evidence is worth paying attention to, and what evidence is of limited relevance or even background noise to what's actually going on in schools. For local decision-making the evidence being gathered is either data from standardized test or from direct observation under the guise of "action research" and usually part of an inquiry grant or teacher collaboration group. The standardized tests are notoriously problematic; considering the history of the FSA tests alone highlights many issues related to the reliability of the tests, the misuse of data coming from the tests, and resistance against these tests (thus affecting results) by teachers, parents, and students themselves.

The direct observation method is also problematic, especially when the data is being gathered by practitioners with little or no research background or ability to apply statistical analysis. Generally, outside of actual research by universities, the wide range of inquiry and "action research" that is conducted in K-12 schools by teachers themselves (not dissimilar to what happens in corporations and some industries) is not guided by any ethical review or peer review. This has consistently resulted in multiple layers of causation errors -- mistaking correlation for causation. When false causes, or in the least dubious causes and compelling correlations, are established as the basis for making claims about a particular educational practice, they become part of the narrative for what's going on in schools, a narrative that is perpetuated among new teachers arriving in the schools and among the students themselves. For example, in one school growth plan I reviewed, there were the results of "study" to gauge the effects of a series of lessons in a newly designed unit on the ability of students to acquire and use vocabulary in a beginner French course. The study used a pre-test before the new unit was taught, and a test afterwards. The results showed (and celebrated) a 28% improvement in the student's vocab skills based on raw test scores. What the summary didn't consider was that almost any group of students who knew nothing about a topic would likely know something after sitting through a dozen lessons on that topic. The study didn't consider how this data compared with student progress before the new unit was used; one would assume that things would be collapsing if there was not some significant improvement in vocabulary in any beginning French class after a series of lesson designed to teach vocabulary. The real kicker was in the data. It turns out that the group being studied averaged 19% on the pre-test and 47% on the post-test. Essentially, the new unit did not bring the students up to a passing grade for the course expectation related to vocabulary. That was all some time ago, but the hasty nature of in-house research is still a common feature in school district across the province. Luckily their hearts are in the right place -- they carry on this work because they wish to improve results for students, but their heads need to catch up by creating more partnerships with actual researchers.

Whether on the local scale, in setting school district priorities, school-based growth plans, and even personal teacher plans for improving their practice, or at the provincial scale, in designing and implementing curriculum and related educational policy, there is a constant return to "what is the evidence telling us." This seems like a healthy approach, but runs into trouble when there is disagreement on what evidence is worth paying attention to, and what evidence is of limited relevance or even background noise to what's actually going on in schools. For local decision-making the evidence being gathered is either data from standardized test or from direct observation under the guise of "action research" and usually part of an inquiry grant or teacher collaboration group. The standardized tests are notoriously problematic; considering the history of the FSA tests alone highlights many issues related to the reliability of the tests, the misuse of data coming from the tests, and resistance against these tests (thus affecting results) by teachers, parents, and students themselves.

The direct observation method is also problematic, especially when the data is being gathered by practitioners with little or no research background or ability to apply statistical analysis. Generally, outside of actual research by universities, the wide range of inquiry and "action research" that is conducted in K-12 schools by teachers themselves (not dissimilar to what happens in corporations and some industries) is not guided by any ethical review or peer review. This has consistently resulted in multiple layers of causation errors -- mistaking correlation for causation. When false causes, or in the least dubious causes and compelling correlations, are established as the basis for making claims about a particular educational practice, they become part of the narrative for what's going on in schools, a narrative that is perpetuated among new teachers arriving in the schools and among the students themselves. For example, in one school growth plan I reviewed, there were the results of "study" to gauge the effects of a series of lessons in a newly designed unit on the ability of students to acquire and use vocabulary in a beginner French course. The study used a pre-test before the new unit was taught, and a test afterwards. The results showed (and celebrated) a 28% improvement in the student's vocab skills based on raw test scores. What the summary didn't consider was that almost any group of students who knew nothing about a topic would likely know something after sitting through a dozen lessons on that topic. The study didn't consider how this data compared with student progress before the new unit was used; one would assume that things would be collapsing if there was not some significant improvement in vocabulary in any beginning French class after a series of lesson designed to teach vocabulary. The real kicker was in the data. It turns out that the group being studied averaged 19% on the pre-test and 47% on the post-test. Essentially, the new unit did not bring the students up to a passing grade for the course expectation related to vocabulary. That was all some time ago, but the hasty nature of in-house research is still a common feature in school district across the province. Luckily their hearts are in the right place -- they carry on this work because they wish to improve results for students, but their heads need to catch up by creating more partnerships with actual researchers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed