| Place Matters We know this on many levels, from our connections to the people, places, and lands in which we dwell — ordinary and extraordinary — and the on-again, off-again relationship that we have with the more-than-human world. Our longing for nature has deep roots in the childhood magic we experienced while playing in the water, hiding behind trees, listening to the crunch of our boots in fresh snow, or watching bugs scatter from under a turned stone. In light of the converging environmental crises we face, and the call from the earth itself for a more sustainable relationship with us, it is also an imperative connection, and on the minds of many educators. Place-responsive practices are closely tied to outdoor learning, nature play, land-based teachings, Indigenous perspectives, and education outside the classroom. These practices are not new, but are being taken up with such enthusiasm in BC that we should really know how they are rooted in lived experience of educators and pedagogies of place. We should also learn about the soil – the conditions in which these practices flourish and the challenges, the risks and rewards that place-responsive educators encounter, and the dynamics of practice that emerge as educators respond to place with their students. | The draft version of my PhD Research Study website is now online: https://www.placeresponsive.ca/ |

|

0 Comments

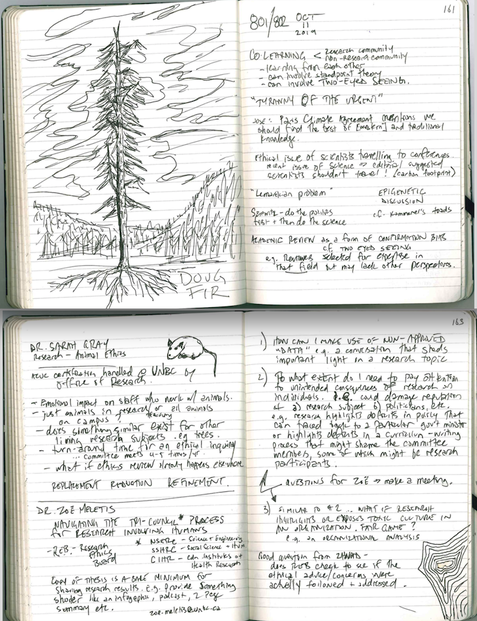

Most important things in my life have happened near or under a Douglas Fir tree – Pseudotsuga menziesii– or a Doug-fir as many of us call it. This present adventure -- a change in job and a return to school as a student -- is no exception, and is reinforced now by the view from my office at the University of Northern British Columbia on a September morning out to a second-growth stand of Doug-firs, the smallest movement there hinting at a breeze, a breath in the forest.

Walking there, at the edge I can see I am entering a managed ecosystem; some stems have been thinned and the woody debris cleared away, and evidence of a logging history and crisscross of humans and their litter is written on the ground. It is perhaps too close to campus to be called wild, but just a few metres into the stand, the sounds of the university recede and older sounds come through the firs and the willow shrubs. Here, the stand is looking more familiar, with bunchberries and wintergreen and pipsissewa poking through the red featherstem moss that carpets the forest floor. Here, a mushroom brings word of the underground network of fungal mycelium, threads that connect root to root, cycle nutrients and biochemical advice from tree to tree. The mycelial network is likely thriving after whatever setback it faced when this stand was first logged -- the trees are sharing secrets in the soil (Wohlleben, 2015). Some of the earliest work that established how trees talk to each other through mycorrhizal associations was done amongst Doug-firs (Toomey, 2016); they have been since, perhaps always, sharing some of their secrets with humans who have been willing to listen. Knowing this for some time, when I walk here, I am aware that a community is at work, sending signals about kin, climate, and food from fir to fir. From a lifelong fascination with maps, stories, and local geography, I begin to see this as a landscape. In the etymological sense, a landscape is a construct, a land-based representation or portrayal – the ship part (OE scype) refers to an appointment, ordination, or creation (as in a fellowship) rather than a ship (OE scipian) that sails on the seas (Little, et al, 1955, pp. 1874–1875). A ship – an appointment, ordination, or creation. What is being represented here? What layers in the physical and cultural landscape are seen and heard now, and what layers are hidden in this portrayal? What stories are held in place by the humus, stored in the submesic soil in wait for a telling, or being told right now in language I cannot understand? Here, the sightlines of academia are still present, with the sound of a building’s HVAC system coming through the trees like water over rocks, and here is evidence of recent silviculture and what appears to be the remnants of a bike jump; but not long gone are signs of industrial forestry and previous land uses. Here, perhaps, was a hunting trail or berry patch visited by the Lheidli Tenneh; maybe they will be here again when the berries come back. Here, I walk on moss and fir needles. Below the litter is podzolic soil, and deeper still, glacial till, sculpted into spoon-shaped drumlins by the slow violence of ancient ice, and then softened by cold waves in a glacial lake 10,000 years ago. These layers have contributed to the identity of people, place, and land on this campus, this community, this region. These stories, happening many times, are how places are formed (Stafford, 1987), and are all part of what surfaces when the geographer in me asks “what is where, why there, and why care?” (Gritzner, 2002). But at this moment, this geographer’s mind almost misses what the Doug-firs are asking of me, carried up from the great fungal threads in the podzol and shipped through the understory by the smell of earth on the small breeze: “what appointment are you seeking here, to what work are you ordained, and what do you hope to create?” This possibility of place, this question from the landscape itself -- a call to ordination from the firs -- is at the root my research. It is also a question that new teachers encounter as they begin their work with students and sort out the kind of pedagogy they wish to establish and what value they hope to find in it. In turn, their students ask similar questions, a wandering about through educational landscapes in search of a path, in search of a horizon. For many educators, a teaching practice that is drawn to place as site and source of learning is an intentional act to engage the questions of their landscapes, to situate and establish their own identity as people who are called to teach, create, and make sense of the paths they walk and the “horizons of significance” they envision (Taylor, 1991), to know who they are in this space. My own path here, to the Natural Resources and Environmental Studies (NRES) PhD program at the UNBC, began in September 2019 after a 23-year career in K-12 public education as a Social Studies teacher. The first year in this interdisciplinary program featured coursework on the philosophy of science, frameworks and critical considerations for conducting and communication research, and interdisciplinarity. Since the 2004 completion of my Master’s degree in Education from Simon Fraser University and throughout my teaching career, I have been interested in research into Geography education in K-12 schools, decolonizing schools and pedagogy, place-responsive teaching and learning, and the role of student and teacher storytelling in Social Studies. This interest has been expressed in my teaching, most notably in student inquiry projects that explored self and the world in the context of history, geography, heritage, and culture. That was not always the work that I was appointed and paid to do, but it was certainly the work for which I was ordained by the path I followed. I have used the first year of the doctoral program and employment in UNBC’s teacher education program to synthesize these research ideas and develop a new pathway towards expanded horizons of significance for myself and other place-responsive educators who seek authenticity, to be "people who are perceived as 'authoring' their own words, their own actions, their own lives, rather than playing a scripted role at great remove from their own hearts" (Palmer, 2007, p. 117). References: Gritzner, C. F. (2002). What is where, why there, and why care? Journal of Geography, 101(1), 38–40. Little, W., Fowler, H. W., & Coulson, J. (1955). The Oxford universal dictionary on historical principles(3rd ed.; C. T. Onions, Ed.). London, UK: Oxford University Press. Palmer, P. J. (2007). The courage to teach guide for reflection and renewal. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Stafford, K. (1987). There are no names but stories. In Places and stories. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University Press. Taylor, C. (1991). The malaise of modernity. Concord, ON: House of Anansi Press. Toomey, D. (2016). Exploring how and why trees ‘talk’ to each other. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from Yale Environment 260 website: https://e360.yale.edu/features/exploring_how_and_why_trees_talk_to_each_other Wohlleben, P. (2015). The hidden life of trees: What they feel, how they communicate - discoveries from a secret world. Vancouver, BC: Greystone Books. An earlier form of this "Welcome" was shared with the incoming cohort in class on Sep 18, 2020. Hopefully some useful tidbits here:

Northern BC Graduate Students' Society Great information and supports for new students on and off campus -- http://nbcgss.ca/ Supports for PhD Research UNBC has many website and human resources to help you out. One of the best resources is the Research Help Desk at the UNBC Library -- receive expert guidance in-person, online, email, and by phone. https://library.unbc.ca/research-help. The UNBC Library also has a Writing Help Desk. Naturally, there are thousands of websites out there that offer advice for PhD students. Here is one I found particularly useful: http://www.raulpacheco.org. Scan through the blog posts to find a topic that matches your need: http://www.raulpacheco.org/blog/. Raul’s Twitter feed is also excellent: https://twitter.com/raulpacheco. Program Timeline Highlights These were some timeline items that were important for me last year, aside from the coursework in 801-804. Keep in mind, though, that you are each of your research paths will look somewhat different. Most of you are no doubt further ahead in terms of your specific research topics than I was when I began the program, and many of you will be involved in data collection and research experiences before your candidacy.

Although a PhD is serious business, and it is not your first time engaging in academic work, this is still about learning and growth. It’s alright to be unsure about things, to have questions about everything, and to learn from mistakes. Be open with your supervisor about where you are in your learning trajectory. Stay curious and realize there is a whole community of teachers and students alongside you in the journey, inside and outside of the NRES program.

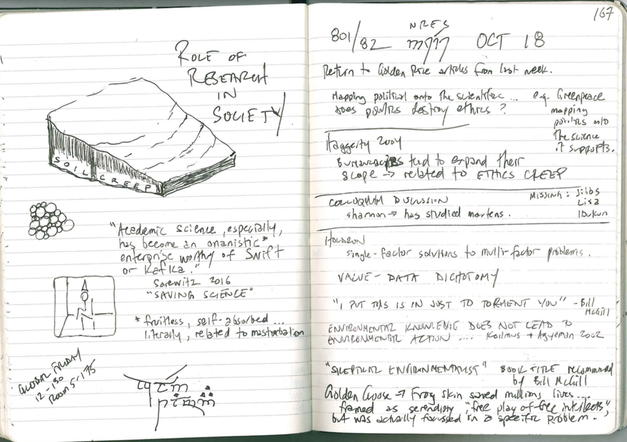

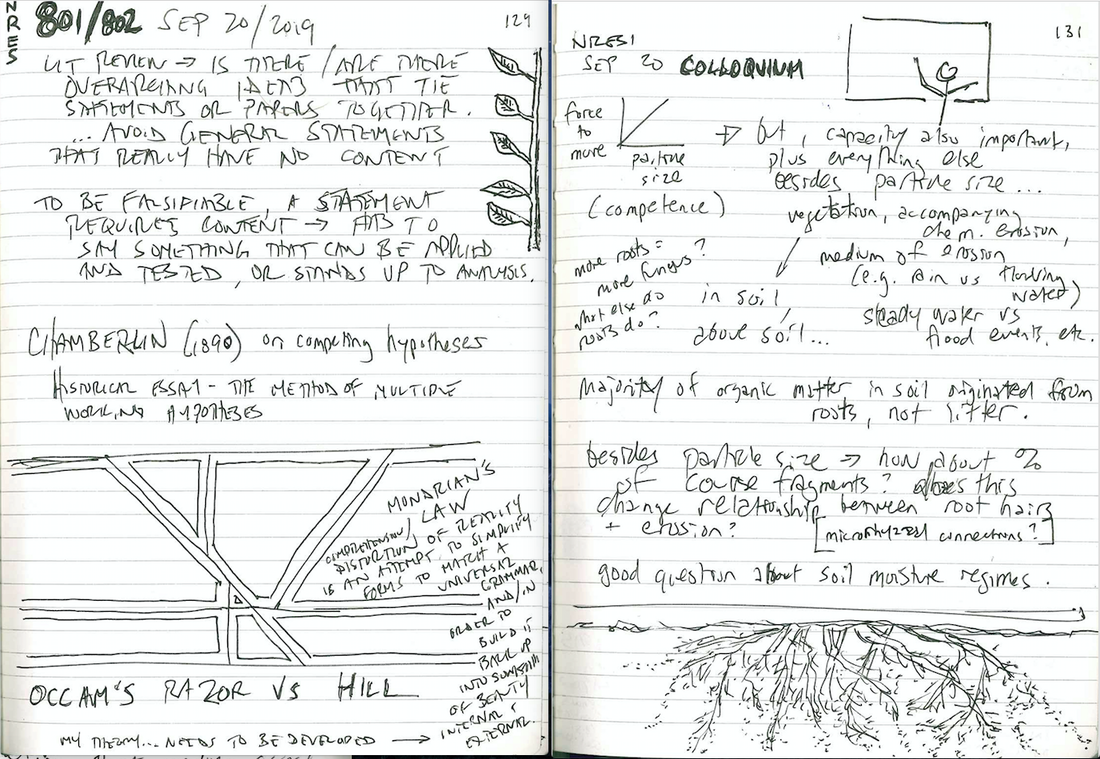

Feel free to stay in touch -- I hope to meet you on campus before too long. I’m sure you are all looking forward to experiencing a true Canadian winter! Our final class discussion moved through some student-selected topics that we did not get to before UNBC job action interrupted our semester. One of these topics was about collaboration between industry and and academia, another on data-dredging and salami slicing (stretching the same data over multiple studies and papers), and manufactured uncertainty.

Sadly, the tactics for manufacturing uncertainty identified by Boan et al (Boan et al. 2018. From Climate to Caribou: How Manufactured Uncertainty Is Affecting Wildlife Management. Wildlife Society Bulletin 42(2):366–381) are too familiar to anyone who pays attention to environmental issues:

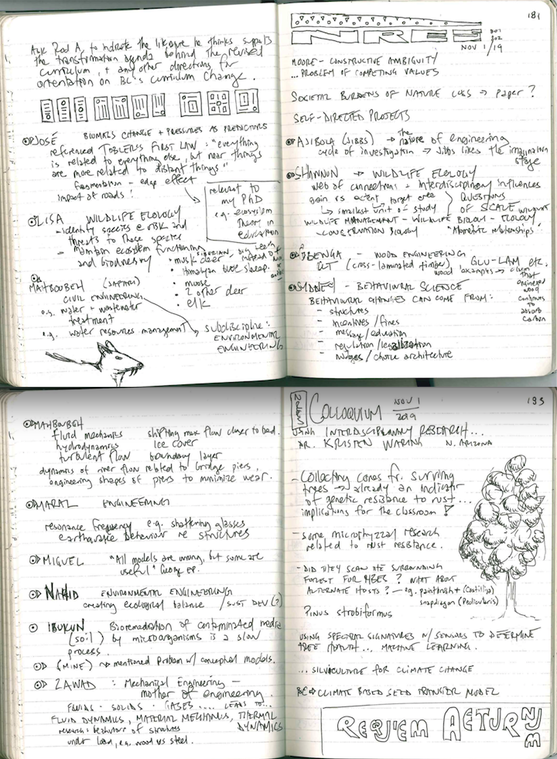

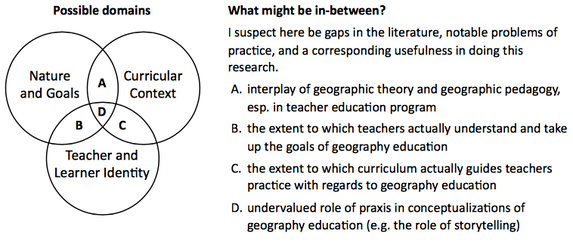

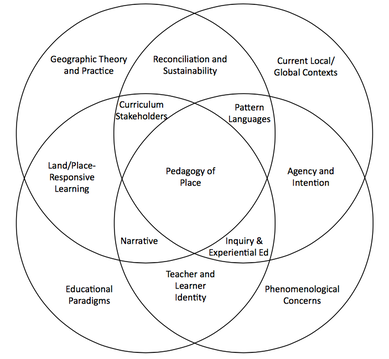

This brings me back to questions of neutrality and whether science can withstand politicization. Wouldn't it be great if our political culture was such that politics took on the burden of asking whether or not it can withstand scientification. In other words, political decisions would have to go through a scientific review process similar to the function provided by the Canadian Senate. To be fair, Senate Committees regularly call in experts to testify, including scientists, but I like the idea of this being a more formal arrangement. Alas, this plan is as subject to bias and corruption as any other, so perhaps we are best served by there being an ongoing dialogue, even if it is strained, between scientists and politicians about who should decide the best course of action on environmental issues. One other gem from the class was a comment from Dr. McGill about the benefits of ignorance... this topic has always intrigued me, particularly as it relates to the unwillingness of otherwise intelligent people to engage on environmental issues. A personal version of Boan et al's tactics for manufacturing uncertainty has become the new normal for large swaths of our society, perhaps adding "too difficult" the list. I once learned a phrase in Latin (I remember it as difficultatis patrocinia praetexis segnitae) that translated as "we make a pretext of difficulty to rationalize sloth." Could be an epithet for the age we live in. This class was a wonderful opportunity to hear about the kinds of research, questions, concerns, passions, and areas of interest that resided in the lives our NRES cohort. I especially like the quote shared by Miguel: "all models are wrong, but some are useful." I used some of my presentation time in this class to talk about the problems with conceptual models as well. Like metaphors, conceptual models can conceal as much as they reveal. I have been experimenting with a variety of conceptual models, some practical, some abstract, that might guide me into my PhD research and help generate questions. On the questions front, the process of conceptualization has ben rewarding. The crops of questions have been abundant. However, the models have been less productive at actually laying out the steps I need to take to move past my questions and into research design. I'm not particularly worried about this -- I am in a nerd's paradise surrounded by excellent questions and a fool's sense of a large expanse of time still in front of me. In terms of abstract conceptual models, I am considering how various representations of tress might serve a purpose (c.f. Mondrian's Law). The Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) is an attractive candidate. Most of the important things that have happened in my life have happened under a Doug Fir. Below are some representations of two "practical" conceptual models I have used to push my research topic along... practical at generating questions, anyways. The documents these are taken from are linked in the blog's right-hand side-bar. From the second conceptual model I extracted four axes that related to tensions within my intended area of study:

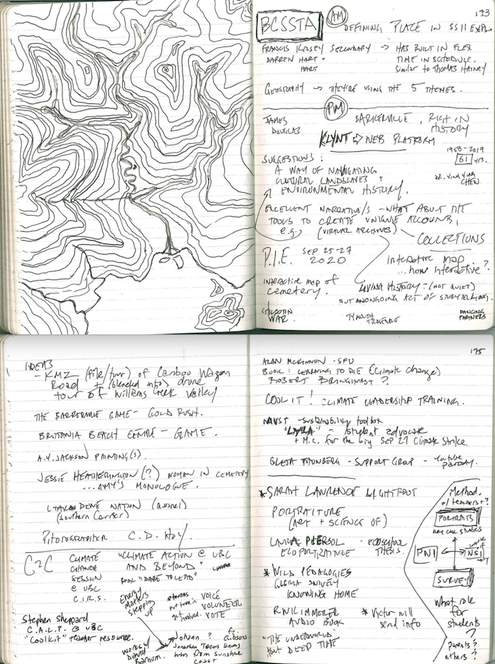

I missed class on Oct 5th in order to attend two conferences in Vancouver. While I regret missing any class, this was an important time to "fill my bucket" and connect with colleagues around issues that are important to my work. As an executive member of the BC Social Studies Teachers' Association, I also had a stake in how the conference turned out. I've included notes here to highlight the degree of interdisciplinarity that exists in the world of a secondary Social Studies teacher. Here are some of the interconnected parts that I can read from just these notes based on three workshops I attended:

First of all, I must report some shock when coming across a word I did not know in a reading by Sarewitz where he suggest that academics science has become onanistic (Sarewitz, D. 2016. Saving Science. The New Atlantis, Spring/Summer, 2016 pages 5-40). Onanistic means fruitless, self-absorbed; literally it is related to masturbation. So I'm learning that the trick to swearing, ribald humour, or other forays into matters profane in academic writing necessitates the use of polysyllabic latinates in replace of more gritty hearth-words. In this case, my assumption of Latin origins was not correct; onanistic is derived from a Biblical reference. Onan was a son of Judah, the guy who didn't want to father a child with his brother's wife so he pulled out of the arrangement, so to speak.

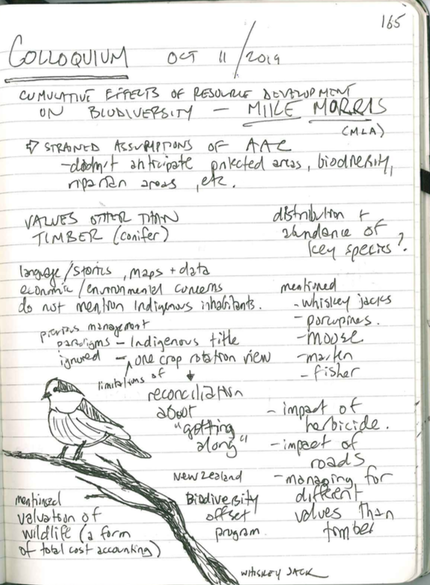

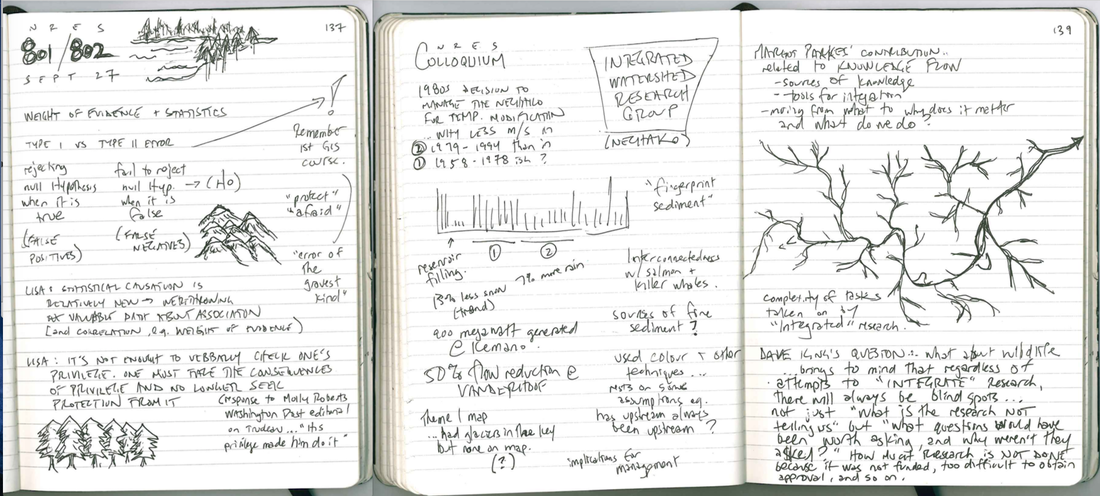

On to more practical concerns, I was pleased to read Holdren's arguments for the role of science in society (Holdren, J.P. 2008. Science and technology for sustainable well- being. Science 319: 424-434). His explanation of the three pillars (see graphic below) forms an excellent description of human geography (the first two) and physical geography (the last one) as they might be taught in secondary schools. This will be useful for my own research to frame the portion of my literature review that deals with the nature of Geography as a discipline. Taking a look at my copy of the article, and others, I see they are dotted with N.B. which is my cue to come back some time and consider the implications of our course readings and discussions for my own research. N.B. stands for noto beni, which is Latin for "note well." Just when you think we can dispense with Latin, it finds a way to be useful again. This presentation engendered a wide range of responses from the audience, some of which I could gather from open questions and comments, some of which I gleaned from conversations afterwards. These responses included a basic satisfaction that a politician was paying attention to these issues, an appreciation for the experience that Mike Morris brought to the topic, and revulsion that someone in a position of power and influence only seemed to come to the realization of the serious impact of resource development after his power and influence has waned. I think I can own the latter two of those sentiments, an appreciation for his decades of ecological observation in the region, and the bitter taste one gets when a politician talks about how they tried to get an issue on the radar of government but it just wasn't on the priority list. I was also concerned that Indigenous concerns (e.g. land title, resource decisions) seemed to be in afterthought in the presentation, that reconciliation was simply about "getting along." A key point Mike made was to talk about the strained assumptions of the Annual Allowable Cut (AAC). For too long it failed to anticipate protected areas, biodiversity, riparian areas, and so on.

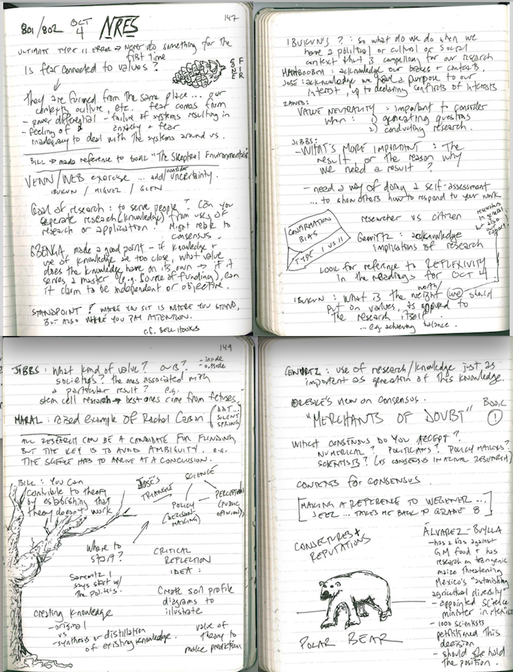

My reference points for industrial forestry go back to my own time working in the woods in the 1980s and 1990s. During the four-month summers between years at university, a couple of longer 8-month stints, and as a transition to teaching, I tried my hand at many forestry jobs: cone-picker, herbicide applicator, research assistant, treeplanter, compassman, surveyor, and finally as an ecosystem geographer, a fancy way of saying that I dug soil pits and classified plants. The range of resource ethics I had to choose from back then were limited, essentially variations on exploitation vs conservation. Resource management has taken many turns since then, and with the recent passage in BC to support the implementation of UNDRIP, I don't think we can go back to the old resource ethics, exploitation vs conservation. There are layers of complexity to consider now. There were many compelling themes in this class, from "does fear drive research choices?" to "what role should stakeholders play in research design?" I was interested to learn about some of the ethical constraints that are place on research. These have strong reasons for being in place, but also serve to make certain kinds of research less desirable than others, especially for students and early-career academics who may want to get going quickly on research projects. I am intrigued that research that does not involve humans or animals does not require ethical review. Might this change in the future? Surely there are areas of research that have serious implication for humans, where the research results may shed light on a problem or perhaps expose groups of people to some form of harm, job loss, a devaluing of a culture, collapse of markets, and so on. For example, convincing research on the case for a particular geoengineering technology to be used to impact the atmosphere could lead to a dramatic shift in the agricultural potential in a specific region. The people who live there, do they have a voice in this research? Perhaps all research should undergo an initial ethical review, and the ones that meet the threshold for an assessment move into the queue for further scrutiny.

The presentations/Q&A by Dr. Sarah Gray and Dr, Zoe Meletis were excellent. Their goal, to remove fear of (and in) the ethics review process, was met. Here are the question I had after Zoe's session:

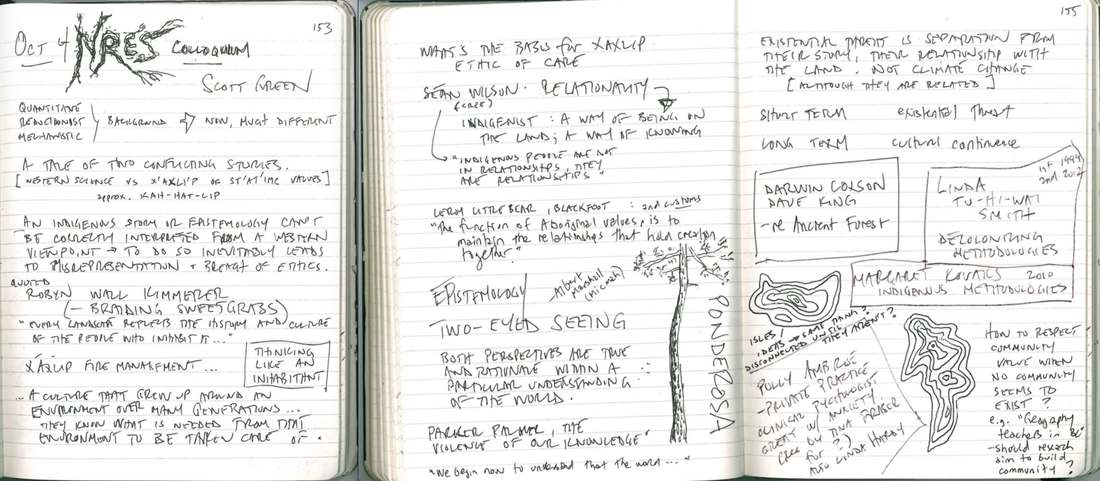

This was one of those talks where I was able to consolidate diverse past learning in a fresh context -- Dr. Scott Green's presentation synthesized a great deal of what I have come to know in recent years about the contrast between Western Science and Indigenous Ways of Knowing. In particular, his use of the term Two-Eyed Seeing was new to me, but as has happened many time this year, within weeks this concept has come up twice more in conversation with others. My overlapping roles as a teacher in the school district, a professional development coordinator interacting with many different networks, someone with a few hats to wear in the teacher training program at UNBC, and a PhD student has led to an amazing "proliferation of resemblances" this year -- everything is starting to blend together, and I am finding the ride exhilarating. One of these resemblances was the reference in Scott Green's talk to Braiding Sweetgrass by Robyn Wall Kimmerer. This book was shared with me a couple of years ago by a colleague and is now part of the readings in the course I teach for the School of Education. Kimmerer develops the idea that Western Science and Indigenous Knowledge can be woven together. She herself is an environmental biologist and member of the Potawatomi Nation, and brings both of these backgrounds into her work, thought, and storytelling. Like on of the access points to our course, she begins her book with a version of the story about the woman who fell from the sky.

A question that came to my mind during Scott Green's talk: If we accept that there are other ways to know the world that Western Science has typically dismissed, then how do we listen to these stories in Education where there is so much pressure to embrace a critical stance, indeed a stance that is suspicious of narrative and is focused on logical order? Two of the articles from this week's readings offered up some ideas for my further consideration. Well, I suppose they all did, but one can only go down so many rabbit holes. The first was the idea that "scientific inquiry is inherently and unavoidably subject to becoming politicized in environmental controversies" (Sarewitz, D. 2004. How science makes environmental controversies worse. Environmental Science and Policy 7(5): 385-403). Sarewitz's recommendation, as I see it, is that we solve (environmental) problems politically based on whatever values are carrying the day, and let science come in on clean-up to address the problem once the political will to act (and presumably the social license to proceed) have been established. I'm not sure I agree with this as a universal principle, but it is one inspiration for our group project's proposal to build a web tool to aid in the establishment of a political will to proceed with a political decision on whether or not to use geoengineering to mitigate climate change. One of the reasons I'm not completely sold on Sarewitz's argument can be summed up in one word: Greta. Over the last year, we've seen the sensational coverage of Swedish teen Greta Thunberg and her "school strikes for climate" as she brings the same message to new audiences: "trust the science, quit talking about climate change, and do something about it." She has highlighted an important Catch 22, perhaps we could call it Sarewitz's Snare: we need to act politically on climate change, because the science tells us this is the right thing to do, but politicians (mainly in the USA) do not trust the science, or believe that scientists should be setting policy.

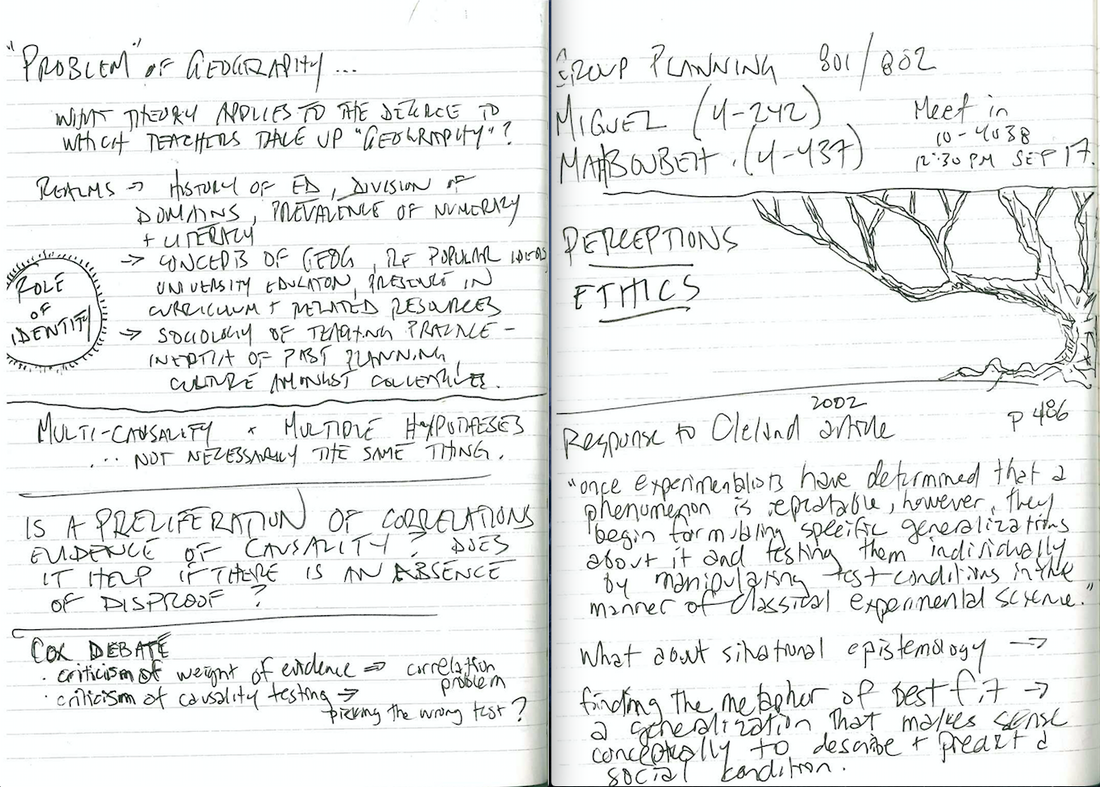

The second idea was about the modern trend towards relativism and partisanship in science as described by Hammersley: "there have been increasing claims, especially among qualitative researchers, that enquiry cannot but be partisan" (Hammersley, M. 2000. “Introduction.” Taking sides in social research: essays on partisanship and bias, London & New York: Routledge). I'm of the view that all research has a bias, or at least a set of assumptions that have some impact on the results. Sometime these assumptions are suspected and researchers go to some lengths to root them out and expose them in their own work, sometime these assumptions are undetected, and sometimes they are deliberate. I think about some qualitative researchers that I know, whose work in the field has provided them with so many reasons to take up advocacy that could not, in good conscience, allow their research not to have a partisan agenda. This is not the same as manipulating research to support a partisan agenda, but it does create challenging questions for these folks about the boundaries between research and advocacy. As it should! I am more comfortable with people with research in a relevant field showing up on a cause than I am leaving this to politicians alone. In m mind, this is especially true for researchers who deal with controversial environmental, cultural, and economic issues. These ideas have some implications for my PhD research. With the addition of ideas from Oreskes and Gerwitz and Cribb (authors of other articles we read), I can see the total set of readings here informing some framing statements for my work around the limits of what can actually be said about teaching and learning, and who should be saying it. these readings also have implications for the role of narrative in educational theory and policy. The locus on control for educational policy in BC is an ongoing debate. In most ways, this control is seated with the provincial government, but in other ways it is also owned by the teachers themselves (via the BCTF) who have rights to bargain key working ad learning conditions in their collective agreement. My research will not likely go there, but it will move about among the various attempts to teach about place, to teach about climate change, to teach about reconciliation. In these areas, a kind of partisanship in the research is a fact of life. Teachers are rarely neutral on climate change and are in fact supported by the government's curriculum (and more recently in the revised Teacher Standards -- see Standard 9) to bring a particular set of values to the table in terms of Indigenous reconciliation. We have been asked to trust the science (the plethora of research about the conditions for Indigenous people in Canada, especially children), trust the work done to inform policy (e.g. TRC Commission, UNDRIP) and jump into the work of of decolonization and reconciliation. Aside from the reality that some teachers don't accept this "science," there are legitimate concerns about how to actually go about this work. This class was mostly a chance to get organized for our group project, but we did have time to consider issues related to evidence and causation. It also featured a memorable quote from our colleague Lisa who deftly summed up a key insight in the ongoing consideration of equity in our society: "It is not enough to verbally check one's privilege. One must face the consequences of privilege and no longer seek protection from it." The debate in literature and the discussion in class on "weight of evidence" vs statistical tests for causation was interesting for me. I'd like to consider how both of these approaches have suffered in the field of K-12 educational policy.

Whether on the local scale, in setting school district priorities, school-based growth plans, and even personal teacher plans for improving their practice, or at the provincial scale, in designing and implementing curriculum and related educational policy, there is a constant return to "what is the evidence telling us." This seems like a healthy approach, but runs into trouble when there is disagreement on what evidence is worth paying attention to, and what evidence is of limited relevance or even background noise to what's actually going on in schools. For local decision-making the evidence being gathered is either data from standardized test or from direct observation under the guise of "action research" and usually part of an inquiry grant or teacher collaboration group. The standardized tests are notoriously problematic; considering the history of the FSA tests alone highlights many issues related to the reliability of the tests, the misuse of data coming from the tests, and resistance against these tests (thus affecting results) by teachers, parents, and students themselves. The direct observation method is also problematic, especially when the data is being gathered by practitioners with little or no research background or ability to apply statistical analysis. Generally, outside of actual research by universities, the wide range of inquiry and "action research" that is conducted in K-12 schools by teachers themselves (not dissimilar to what happens in corporations and some industries) is not guided by any ethical review or peer review. This has consistently resulted in multiple layers of causation errors -- mistaking correlation for causation. When false causes, or in the least dubious causes and compelling correlations, are established as the basis for making claims about a particular educational practice, they become part of the narrative for what's going on in schools, a narrative that is perpetuated among new teachers arriving in the schools and among the students themselves. For example, in one school growth plan I reviewed, there were the results of "study" to gauge the effects of a series of lessons in a newly designed unit on the ability of students to acquire and use vocabulary in a beginner French course. The study used a pre-test before the new unit was taught, and a test afterwards. The results showed (and celebrated) a 28% improvement in the student's vocab skills based on raw test scores. What the summary didn't consider was that almost any group of students who knew nothing about a topic would likely know something after sitting through a dozen lessons on that topic. The study didn't consider how this data compared with student progress before the new unit was used; one would assume that things would be collapsing if there was not some significant improvement in vocabulary in any beginning French class after a series of lesson designed to teach vocabulary. The real kicker was in the data. It turns out that the group being studied averaged 19% on the pre-test and 47% on the post-test. Essentially, the new unit did not bring the students up to a passing grade for the course expectation related to vocabulary. That was all some time ago, but the hasty nature of in-house research is still a common feature in school district across the province. Luckily their hearts are in the right place -- they carry on this work because they wish to improve results for students, but their heads need to catch up by creating more partnerships with actual researchers. Having visited the Pit House near UNBC with my School of Education group a few days prior, I though it would be a good idea to invite the PhD cohort out there as well, in part an orientation to the geography and ecology of the UNBC environs, in part an introduction to the local Indigenous culture -- the Lheidli T'enneh / Dakelh peoples -- and in part as an activity to bring the group together. It's been a busy Fall so far, and one of my few regrets is that I have not made more of an effort to make this group of virtually all international students feel more welcome as special guests in Prince George.

The Pit House came about through a collaboration of local Indigenous leaders and teachers, Indigenous (Lheidli T'enneh) high school students, and an experiential learning class from UNBC. "The pit house the students built is in the Dakelh style. Dakelh translates as the “people who travel by boat” and are the indigenous people from the north-central interior of British Columbia. It’s a traditional winter dwelling historically used by many indigenous peoples around the world" (UNBC). One of folks working on this was Jen Pighin, a colleague and friend of mine. She told me that they named the place "Tsasdil Yoh" which means House of Frogs," because there were so many frogs about when they were building the pit house. Jen encourages visitors to light a little fire, and use this space to reflect and dream, and to learn more about Dakelh culture. So, on Friday, after NRES class, we had a little fire (and lots of smoke) in this unique spot after a leisurely walk on a portion of the Greenway Trail discussing local flora, fauna, and landforms with the help of Roger Wheate. I'm still surprised that I remember most of the Latin names of the local plants after not having used this arcane knowledge for 25 years. For the record I did not name all the plants as we went along, but I did pass on some knowledge I had about Dakelh culture and the Lheidli T'enneh in particular. We didn' stay long, most of the group wanted to carry on and see Shane Lake. My internal reflection in the pit house, and what I was conscious of even while I was talking, was that my background as a Social Studies teacher and a white settler who has spent almost his entire life in this city and region, has conditioned me to frame discussions and characterizations of local Indigenous culture in the past tense. It has always seemed so much safer to me to compartmentalize traditional culture, ways of knowing, and modes of subsistence in an academic box of the Past, and treat modern Indigenous culture, issues, and realities as something different, something to be problematized or "solved." I think this bias goes deeper in that where there are obvious links between the past and present, I have perhaps tended to see these as symbolic, or manifestations of "creeping determinism" (hinging an argument on hindsight), rather than actual instances of historical continuity. The deep problem here is that Indigenous attempts at reclaiming culture or reviving traditions can be treated as exercises or experiments, and not serious attempts to move into a new cultural norm that is still in sync with the past, with the ancestors. I sense that this bias is not unique to my own trajectory, but is systemic, and is a real barrier to reconciliation. It is not unlike the impact of residential schools that tried to create a sharp break between the past and present. I am resolved to break down this bias and work at seeing the past and present linked through efforts of reconciliation. I am reminded of a graphic I have used with a School of Education class from author Jennifer Katz's book Ensouling Our Schools that compares Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs with a Kainai First Nations concept of actualization through Cultural Perpetuity. In my mind, decolonizing our institutions (and for me, a teaching practice) is to make some serious space for Indigenous people to bridge their own past and present, to weave traditional ways of knowing with modern concerns and daily life in a way that promotes personal wellbeing (in every sense, including economic) and cultural perpetuity. One of the things I like most about being a student is that coursework, specifically class time, provides a rare opportunity to think abstractly. So many of the tasks that fill my week are practical or purpose-driven in some way, but the interplay of ideas, dialogue, reading, and provocations that feature in a good class are like a spa visit for my brain. Of course, there are expected outcomes, assignments to complete, curriculum to absorb, and designated discussion topics of the day that command one's attention while in class, but the mind is a big enough place to wander around and outside of the syllabus, especially when the main expectation in a class setting is to think. One of my colleagues at D.P. Todd Secondary, where I worked from 2003-2018, used to place a note on his wall for students to see: "How have I invited you to think today?" This was both a powerful invitation for students to become engaged in class, but was also a significant commitment on the part of the teacher -- he was in fact holding himself accountable for facilitating lessons each day that engage minds. Unfortunately, there are many secondary classrooms where this is not the case. There might as well be the same sign in the wall in our NRES classroom, because here I have been invited to stretch my thinking, not just forward (i.e. consideration of new ideas of engagement with concepts from fields that are outside of my experience), but backwards -- the sense that everything I have learned in 50 years about the old, science, nature, ecology, education, society, geography, language, philosophy, etc., is being called upon to synthesize responses. A process most enjoyable. For the most recent class, my thinking went a little more whimsical, hence Mondrian's Law.

Mondrian's Law, an invention of mine as far as I can tell, is the result of my fixation on Simplicity from last week's class and readings, and perhaps a response to drawing some intersecting lines on paper or a consideration of the difference between Occam's Razor and Occam's Hill. Mondrian's Law is an attempt to set a scene for social science methodologies that embraces the abstract. Who's up for blurring the lines between theory and practice? This idea, from all appearances, is inchoate at best, barely set free from the barn. Piet Mondrian was a brilliant Dutch artist who developed an abstract style of painting that sought to access universal truths and yet remain in tension (or dialogue?) with reality. Here is a link to a good bio <Guggenheim on Mondrian>, and sense of the art that is most often connected with Mondrian <google search: piet mondrian art>. I associate Mondrian with trees and his wonderful geometric representations of them, and have often thought that if I ever took art more seriously (speaking of inchoate) I would start with Mondrian because I love trees and been enamoured with what he has done with them. The Law, as I imagine it, is about the comprehension and distortion of phenomena in an attempt to simplify forms such that they are resonate on the same frequency as universal grammar (c.f. Chomsky) or create what the architect Christopher Alexander popularized as "Pattern Language," and are then built back up into something of internal and external beauty that reflects a more poetic, and yes, a simpler explanation, than direct representations of phenomena. Basically, Mondrian's Law is about stripping down reality to basic elements as they are perceived by participants, and using those basic elements to recreate portrayals of reality that have a deeper connection for the participant than what they get from direct observation. I suppose this could be Picasso's Law as easily as Mondrian's. What;s that quote from Picasso? "We all know that art is not truth; art is a lie that makes us realize truth." I'm hoping this is sufficiently weird that it has not already been theorized by someone else. On the other hand, it is extremely common in art, from what I can gather, although it may be a newcomer on the social science scene. I'll need to sit down with a bona fide phenomenologist to find out for sure. During this class, we spent a considerable amount of time discussing simplicity. I can certainly understand that simplicity is held as a virtue in most scientific fields, Occam's Razor and all that, but I find myself trying to generate arguments against this virtue, perhaps because of my experience with bureaucracy, or as a result of cogent arguments that question the limits of Occam's Razor. At many times during my career I have seen simplicity used as a weapon to silence critics of various proposed changes or "improvements" in public education. A decision to close this program here or cut funding there is tied to "simple facts" but unfortunately using "simplistic arguments" to justify the use of these facts, and not others. Too often, simplicity, particularly in a policy and governance context, is used as a shield to prevent others from prying into how little work was done to establish the facts, or how thin the grounds are for making claims about the veracity of those facts. Without getting into details, I got to see this pattern repeated many times at the local level, sometime with a front row seat, sometimes from afar. If I had to offer a defense of this practice, that is, the oversimplification of cases and contexts by discouraging anything more than superficial analysis and reliance on the first set of facts that present themselves on a preliminary investigation of the thing being decided on, I would suggest that educational leaders have virtually no training in the kinds of fields that would normally offer challenges to perfunctory treatment of issues. We need more philosophers to become educational leaders!

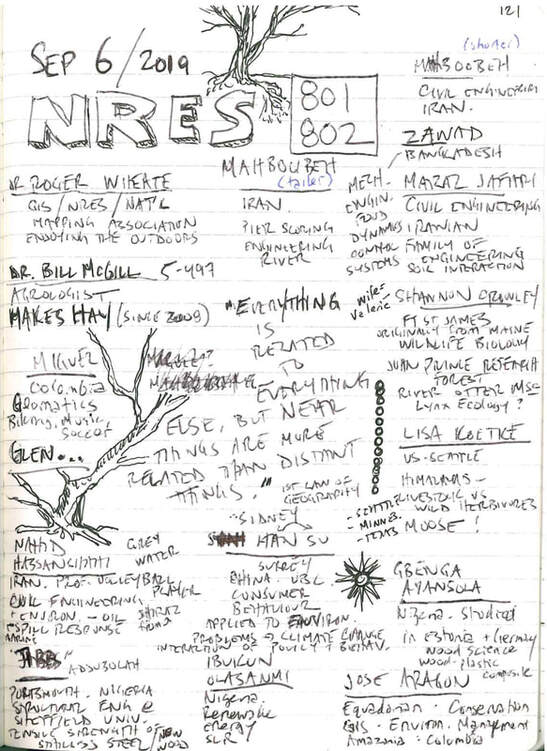

This may seem tangential to the notion of simplicity as discussed in the class, but it is important to know about the association I bring to this subject if I hope to dispel or at least challenge my pre-concieved notions and biases. It also raises the question: if important decisions have been made in education by masking complex issues with a cloak of complexity, then what else have we been sold because someone (a company, a group of experts, a government) has offered up a Simple Truth or conclusion about something because it was the easiest path through a bureaucratic quagmire. At any rate, I believe it is as healthy to have a robust skepticism of all claims to simplicity as it is to seek out simple theories or models of best fit. Speaking of bias, I was stopped by this line from one of the articles we read: "Preferences for simpler theories are widely thought to have played a central role in many important episodes in the history of science." (Simplicity in the Philosophy of Science from the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). The history of science, here and elsewhere, is probably taken to mean the history of Western Science. I can't help but wonder about the correlation with colonial, andocentric, and Eurocentric perspectives. Does the use of a contrasting perspective to traditional Western Science, feminist standpoint theory for example, challenge the appeal to simplicity as a virtue and use of simpler theories? What is simplicity, again, is masking complexity because it contains perspectives and interpretations within existing paradigms? I wrote two quotes at the top of my copy of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on the noted social and political Viennese philosopher Karl Popper..I'm really not sure if it was his words or something I picked up in class: "science must begin with myths, and the criticism of myths" and "science may be described as the art of systematic over-simplication." Taken together, these quotes could furnish a course-length study on their own, but I appreciate how they frame, for myself anyway, the important bookends of a study on the faith in simplicity in scientific research, particularly of a social kind applied to policy and culture. I made a note to return to Popper's disdain for historicism. I sense that many Social Studies teachers are unwitting acolytes of historical determinism, so perhaps Popper will suggest a cure. I should also note that the most interesting word I learned while reading about Popper was amanuensis, as in Popper's wife was also his amanuensis. It means secretary. Day one with a new cohort, and there was some expected nervousness and excitement on the faces as they moved into the classroom. Not all would make it for the first class -- there were apparently some problems with travel -- but we would eventually become a group of fourteen. This reminded me of the party of 13 dwarves and one hobbit that set out for the Lonely Mountain in Tolkien's beloved story The Hobbit. I would not hazard a guess as to who is who in the group... not all the dwarves met with a happy fate. The fifteenth member of that party was of course the wizard Gandalf and we have our own wizard in the form of Dr. Bill McGill.

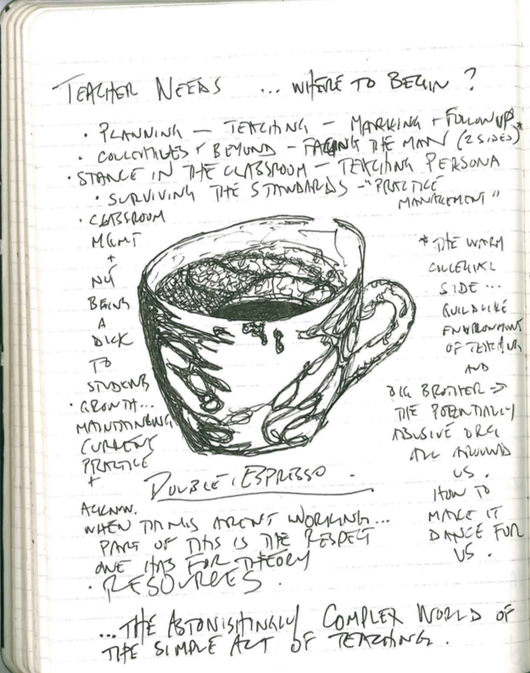

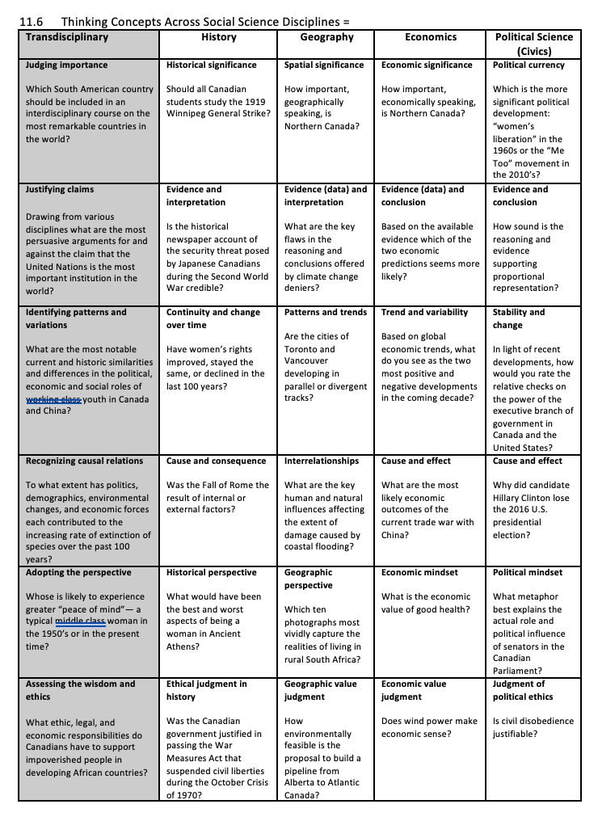

We are an international crew. I'm from Canada, a high school Social Studies teacher with some forays into other "Educational" work and some distant but memorable roots in forest ecology. Mahboubeh, Mahboobeh, Maral, and Nahid are all engineers and from Iran. Shannon and Lisa are both Americans by birth and connected to wildlife biology, but have travelled, lived, and studied in many places. Gbenga, Ajibola (Jibbs), and Ibukun are from Nigeria, with some detours, and are also engineers. Sidney is originally from China, and has a diverse research interests that I'm still not sure how to characterize. Jose is from Equador and is involved in environmental management. Miguel is from Colombia and is involved in geomatics. Zawad is from Bangladesh and completes our list of engineers. Dr. Roger Wheate is the Acting Chair of the NRES Grad Program and a frequent guest in our class; I suppose he is competition for the role of Gandalf. Dr. Bill McGill is an excellent fit for our group. I really appreciate the course design and emphasis on thought and discussion; this may not be everyone's cup of tea but I'll drink it any day. This ages me a bit, and Dr. McGill as well, but I must say this experience has reminded me of my undergrad days at UBC in the late 1980s and early 1990s, sitting in a classes and listening to sages, trying to keep up with powerful ideas and challenging questions. I knew we were in for a great adventure when Dr. McGill set up his juiciest questions with "let me torment you with this" or "let me harangue you with this." NRES 801 and 802 have been fully integrated for our cohort. This means that we will examine issues in biophysical sciences and social sciences through similar lenses. For example, problem-solving in the biophysical sciences might relate to use of technology, whereas in the social sciences it might relate to policy development. For me, as someone squarely from the social sciences (even my approach to teaching physical geography to high school students centred on humanistic and human-environment adaptive perspectives), standing upright at the mirror of hard science is daunting. Do I belong here? Does my limited background in chemistry, physics, and mathematics make me look fat? (I am standing at a mirror, after all). Knowing that my colleagues, mostly engineers, are thinking the same thing about social sciences gives me pause to realize that this will be ok. As I'm understanding the unfolding syllabus, this program is not so much about diving into the sciences themselves but about examining critical issues related to these sciences, such as bias, ethics, methodological considerations, and interdisciplinarity. I'm finding that the biophysical research and social science research have a lot in common in terms of philosophic issues, but usually go in different directions when it comes to methodology and appeal to objectivity. On this last point I must add my amusement about how so many researchers in my field of Education (e.g. K-12 education, K-12 Social Studies education) are on a quest for some objective stance on best practice, for the most effective way to plan, teach, and assess. If we had as much respect for subjectivity and less trust in elaborate frameworks, perhaps we'd really get somewhere. This sounds like a preference for a form of dead reckoning over a more scientific approach to navigating education, and that is indeed what I mean. It is the stories we tell about where we are going in education that are proving most useful for new teachers, a series of course corrections with shifting goals, a sense of abandonment to the process and trust in our own values that guides our course and fills in the map. I feel as if I have not explained myself too well, here, so I hope to return to this topic. To me it is about exploring the dissonance between educational philosophy and practice that has become pronounced with the introduction of new K-12 curriculum in BC. Q1: What is a principle, law, or fundamental concept that is generally accepted in my discipline? First , what’s my discipline? Education -- an “educator” or something more specific? I teach Social Studies, I teach teacher candidates, I have an administrative role related to teacher professional development, I have a leadership and curriculum design role in both teacher education and social studies education, I have official and unofficial roles as a advocate for and within K-12 public education for both public education itself and also specific curricular and pedagogical issues, and I have a consultancy arrangement that combines all of these things Geography -- not really a geographer in the sense that most would recognize, but very much involved in geography education within and without the context of “Social Studies” as it is understood in the K-12 system. So, for the purpose of this activity I’ll settle on my discipline as secondary Social Studies education and pick the “Big Six” Historical Thinking Concepts (and their counterparts, the Geographic Thinking Concepts). Background - Principles: Various educators have tried to establish principles or laws by which learning takes place, but these are best called theories due the difficulty in proving that singular theories are correct in what is generally recognized as a Sea of competing theories, approaches, and agendas. No unifying theory of learning has proven stable enough to completely drive education at scale and over time (e.g. within provincial or national jurisdictions). Examples of some existing/well-accepted “classic” theories of education (in no particular order):

Background - Laws: Literally -- the School Act, the BC Curriculum, and the Collective Agreement... but in the sense probably intended there are few Laws by which Social Studies proceeds; nothing, at least, that garners anything approaching universal agreement. Certainly there are themes in Social Studies such as the Five Themes of Geography but these are closed to Concepts than they are Laws. See Principles (above) and Concepts (below). Background - Concepts: The most relevant for this exercise appear to be the Historical Thinking Concepts, as developed by Peter Seixas and others at the Historical Thinking Project, that are embedded within the current (revised) Social Studies K-12 curriculum documents and other provincial K-12 curricula across Canada, and the related Geographical Thinking Concepts as developed by Roland Case and others in association with The Critical Thinking Consortium (TC2). While there is some disagreement that these concepts are not the only way to frame History or Geography education (for example, the “Five Themes of Geography” used to be provide a common framework for teachers), they are the chosen vehicle to reframe Social Studies courses along the ideas of “competency-based” education, as opposed to a solely content-based curriculum, which was ostensibly (and arguably) what we had until now . The use of competencies is itself a sort of guiding principle or suggested “Law” in my field, but is, again, a theory that does not yet command widespread agreement, even within the BC education system where it is the theory-du-jour. Q2: What is the basis for such agreement? Why do people in the discipline accept it? What (if any) is the evidence for it? I’ve posed a variant of these questions on twitter to Social Studies teachers in general, and to two "experts" in this field: Dr. Lindsay Gibson in particular, who is a professor of Social Studies Education at UBC, a student of Peter Seixas and deeply involved in the development and suffusion of the Concepts, and was on the curriculum writing team for BC Social Studies, and to Dale Martelli, a well-known secondary teacher of Social Studies and Philosophy, the president of the BC Social Studies Teacher's Association, and also a member of the same curriculum writing team. I asked: “Assuming that the Historical Thinking Concepts are generally accepted as a basis for sound practice in Social Studies classrooms, a) What is the basis or evidence for such agreement? b) Why do people in the discipline accept it?” I’ve also posed these questions to executive members of the BC Social Studies Teachers’ Association. My assumption, of course, is not a certain one but is so close to my intended area of research that I’d be remiss not to start there. While awaiting responses, I’ll make some predictions. Basis for agreement:

Basis for acceptance:

Evidence for suitability of principle, law, or concept:

Update (Sep 7): I didn't get a whole lot of uptake on the twitter end of things, but targeting Dale Martelli and Lindsay Gibson proved to be fruitful. Dale Martelli, The BC Social Studies Teachers' Association president, replied with a detailed challenge to the question (wonderful) and provided me with a list or recommended reading that positioned other "portal concepts" and ways-of-knowing as important for History/Social Studies educators and challenged the universal applicability of Historical Thinking Concepts. In his personal correspondence with me (Sep 5, 2019), he made salient points about how this trend to associate Social studies with Historical Thinking has featured in educational debates for decades, and that his sense was that compartmentalization was never a common pursuit among practitioners. He wondered at the provincial table "why we are not looking at the whole thing from a deeper ontological lens." Predictably, this was met by giggles -- the curriculum process was not invested to solve academic debates within the discipline, it was there to provide something simple enough to be be used by all teachers and consistent with the competency-driven theme being written into all of the other course curriculums. Dale also made a case that our curriculum should not be so focused on skill development and should respond to more of a Building approach to education. As always, my conversations with Dale leave me with more questions than answers. That's a good thing, from my perspective. By the way, here are the articles that he recommended for me -- a nice start for my own research on this topic. Lindsay Gibson, Assistant Professor of Curriculum & Pedagogy at UBC, also replied with a challenge to the question, that Historical Thinking was not necessarily seen as a basis of sound practice. Over the course of a series of related exchange, he share the following graphic that goes some way towards the view that Social Studies is more interdisciplinary that a simple reliance on Historical Thinking would suggest: So, I now feel as if I asked the right question to determine whether my question was valid, and determined that it was not particularly valid! The answer appears to be that there is no solid basis for agreement on how Social Studies education should work, and that the many teachers are perhaps not very well informed about why the Historical Thinking Concepts were picked to headline the new Social Studies curriculum.

Why am I doing a PhD? Probably at the top of my reasons is to model for my family the state of being curious and being willing to set off on an adventure, with or without a hankerchief. My personal and professional identities have always existed somewhere between the realms of Geography and Education, in many senses of both words, and the UNBC NRES Interdisciplinary Program is a great fit for addressing curiousity and furnishing an adventure within these areas. Beyond that, I hope to improve my qualifications for providing support of curriculum development and instruction among Social Studies teachers in BC, and provide more qualified advice and advocacy for K-12 Education in general, including teacher training programs.

As far as the inquiries and potential research themes that create curiousity for me -- at this moment -- I’m interested in storytelling in general, and specifically in the context of Social Studies classrooms (including History and Geography) in secondary schools, and the way in which teachers tend to build narratives (and often support grand narratives) in contrast to historical and geographic thinking concepts which tend towards the critical examination and deconstruction of narratives. These thinking concepts underpin the revised curriculum in BC in the form of curricular competencies, and thus require some kind of stance by educators in terms of curriculum design and pedagogy, as well as a willingness to engage in new learning about academic concepts that may not have been an expectation when they began teaching. Storytelling, however, is a natural resting spot for teachers and students alike, and a source of engagement, satisfaction, inclusion while at the same time cementing certain views of time and place, and creating as many fallacies and biases as it does revelations. Storytelling and critical thinking, therefore, form a sort of dichotomy within Social Studies education; however, these two spheres do not neatly form a binary as they contain both complimentary and overlapping elements, and are informed by other stances that have the potential to make lasting bridges or at least make the differences creative, one of the most important of which is the First Peoples Principles of Learning, but also includes connection to place and expressions of identity. Mapping out the landscape of Social Studies education requires some understanding of the challenges faced by teachers in the planning and delivery of curriculum (and the professional development models used to support their pedagogy), as well as the actual curriculum experiences by students and the outcomes that arise from different philosophical approaches to classroom and curriculum design. In this curricular/geographic/identity context there is a research question lurking, perhaps something to do with the problems of practice that arise when teachers and students engage in storytelling about place. |

Turning StonesBeing An Online Record of How Things are Going in UNBC's Interdisciplinary NRES (Geography) PhD Program.

PDF version of this blog. NRES PhDI started the UNBC NRES PhD Program in September 2019 with a research interest in K-12 Geography Education -- problems of practice and educator response to curriculum change, with a focus on place-based educators in North Central BC.

Glen ThielmannSocial Studies & Geography teacher, dead reckoning the nature & culture of learning, student of maps, Tolkien fan, dad, husband, part Sasquatch, all Canadian. DocumentsResearch Directions v.1 2019.10.08

Research Directions v.2 2019.10.22 Research Directions v. 3 2019.12.13 Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed