Q1: What is a principle, law, or fundamental concept that is generally accepted in my discipline?

First , what’s my discipline?

Education -- an “educator” or something more specific? I teach Social Studies, I teach teacher candidates, I have an administrative role related to teacher professional development, I have a leadership and curriculum design role in both teacher education and social studies education, I have official and unofficial roles as a advocate for and within K-12 public education for both public education itself and also specific curricular and pedagogical issues, and I have a consultancy arrangement that combines all of these things

Geography -- not really a geographer in the sense that most would recognize, but very much involved in geography education within and without the context of “Social Studies” as it is understood in the K-12 system.

So, for the purpose of this activity I’ll settle on my discipline as secondary Social Studies education and pick the “Big Six” Historical Thinking Concepts (and their counterparts, the Geographic Thinking Concepts).

Background - Principles:

Various educators have tried to establish principles or laws by which learning takes place, but these are best called theories due the difficulty in proving that singular theories are correct in what is generally recognized as a Sea of competing theories, approaches, and agendas. No unifying theory of learning has proven stable enough to completely drive education at scale and over time (e.g. within provincial or national jurisdictions).

Examples of some existing/well-accepted “classic” theories of education (in no particular order):

Background - Laws:

Literally -- the School Act, the BC Curriculum, and the Collective Agreement... but in the sense probably intended there are few Laws by which Social Studies proceeds; nothing, at least, that garners anything approaching universal agreement. Certainly there are themes in Social Studies such as the Five Themes of Geography but these are closed to Concepts than they are Laws. See Principles (above) and Concepts (below).

Background - Concepts:

The most relevant for this exercise appear to be the Historical Thinking Concepts, as developed by Peter Seixas and others at the Historical Thinking Project, that are embedded within the current (revised) Social Studies K-12 curriculum documents and other provincial K-12 curricula across Canada, and the related Geographical Thinking Concepts as developed by Roland Case and others in association with The Critical Thinking Consortium (TC2). While there is some disagreement that these concepts are not the only way to frame History or Geography education (for example, the “Five Themes of Geography” used to be provide a common framework for teachers), they are the chosen vehicle to reframe Social Studies courses along the ideas of “competency-based” education, as opposed to a solely content-based curriculum, which was ostensibly (and arguably) what we had until now . The use of competencies is itself a sort of guiding principle or suggested “Law” in my field, but is, again, a theory that does not yet command widespread agreement, even within the BC education system where it is the theory-du-jour.

Q2: What is the basis for such agreement? Why do people in the discipline accept it? What (if any) is the evidence for it?

I’ve posed a variant of these questions on twitter to Social Studies teachers in general, and to two "experts" in this field: Dr. Lindsay Gibson in particular, who is a professor of Social Studies Education at UBC, a student of Peter Seixas and deeply involved in the development and suffusion of the Concepts, and was on the curriculum writing team for BC Social Studies, and to Dale Martelli, a well-known secondary teacher of Social Studies and Philosophy, the president of the BC Social Studies Teacher's Association, and also a member of the same curriculum writing team. I asked: “Assuming that the Historical Thinking Concepts are generally accepted as a basis for sound practice in Social Studies classrooms, a) What is the basis or evidence for such agreement? b) Why do people in the discipline accept it?” I’ve also posed these questions to executive members of the BC Social Studies Teachers’ Association. My assumption, of course, is not a certain one but is so close to my intended area of research that I’d be remiss not to start there.

While awaiting responses, I’ll make some predictions.

Basis for agreement:

Basis for acceptance:

Evidence for suitability of principle, law, or concept:

Update (Sep 7): I didn't get a whole lot of uptake on the twitter end of things, but targeting Dale Martelli and Lindsay Gibson proved to be fruitful. Dale Martelli, The BC Social Studies Teachers' Association president, replied with a detailed challenge to the question (wonderful) and provided me with a list or recommended reading that positioned other "portal concepts" and ways-of-knowing as important for History/Social Studies educators and challenged the universal applicability of Historical Thinking Concepts. In his personal correspondence with me (Sep 5, 2019), he made salient points about how this trend to associate Social studies with Historical Thinking has featured in educational debates for decades, and that his sense was that compartmentalization was never a common pursuit among practitioners. He wondered at the provincial table "why we are not looking at the whole thing from a deeper ontological lens." Predictably, this was met by giggles -- the curriculum process was not invested to solve academic debates within the discipline, it was there to provide something simple enough to be be used by all teachers and consistent with the competency-driven theme being written into all of the other course curriculums. Dale also made a case that our curriculum should not be so focused on skill development and should respond to more of a Building approach to education. As always, my conversations with Dale leave me with more questions than answers. That's a good thing, from my perspective. By the way, here are the articles that he recommended for me -- a nice start for my own research on this topic.

First , what’s my discipline?

Education -- an “educator” or something more specific? I teach Social Studies, I teach teacher candidates, I have an administrative role related to teacher professional development, I have a leadership and curriculum design role in both teacher education and social studies education, I have official and unofficial roles as a advocate for and within K-12 public education for both public education itself and also specific curricular and pedagogical issues, and I have a consultancy arrangement that combines all of these things

Geography -- not really a geographer in the sense that most would recognize, but very much involved in geography education within and without the context of “Social Studies” as it is understood in the K-12 system.

So, for the purpose of this activity I’ll settle on my discipline as secondary Social Studies education and pick the “Big Six” Historical Thinking Concepts (and their counterparts, the Geographic Thinking Concepts).

Background - Principles:

Various educators have tried to establish principles or laws by which learning takes place, but these are best called theories due the difficulty in proving that singular theories are correct in what is generally recognized as a Sea of competing theories, approaches, and agendas. No unifying theory of learning has proven stable enough to completely drive education at scale and over time (e.g. within provincial or national jurisdictions).

Examples of some existing/well-accepted “classic” theories of education (in no particular order):

- BF Skinner -- Behaviourism -- learning takes places through reinforcement and repetition

- Edward Thorndike’s “Laws of Learning” -- readiness, exercise, and effect

- Jean Piaget -- Theory of Cognitive Development (1936) -- Constructivist -- intelligence is not fixed -- discrete stages of child cognitive development

- Lev Vygotsky -- Contructivist -- Social Development Theory -- interrelatedness of social and cultural contexts, individual development, and higher mental processes

- John Dewey -- Constructivist -- active participation by children in their own learning, social context for learning, experiential learning, foundations for problem- and inquiry-based learning

Background - Laws:

Literally -- the School Act, the BC Curriculum, and the Collective Agreement... but in the sense probably intended there are few Laws by which Social Studies proceeds; nothing, at least, that garners anything approaching universal agreement. Certainly there are themes in Social Studies such as the Five Themes of Geography but these are closed to Concepts than they are Laws. See Principles (above) and Concepts (below).

Background - Concepts:

The most relevant for this exercise appear to be the Historical Thinking Concepts, as developed by Peter Seixas and others at the Historical Thinking Project, that are embedded within the current (revised) Social Studies K-12 curriculum documents and other provincial K-12 curricula across Canada, and the related Geographical Thinking Concepts as developed by Roland Case and others in association with The Critical Thinking Consortium (TC2). While there is some disagreement that these concepts are not the only way to frame History or Geography education (for example, the “Five Themes of Geography” used to be provide a common framework for teachers), they are the chosen vehicle to reframe Social Studies courses along the ideas of “competency-based” education, as opposed to a solely content-based curriculum, which was ostensibly (and arguably) what we had until now . The use of competencies is itself a sort of guiding principle or suggested “Law” in my field, but is, again, a theory that does not yet command widespread agreement, even within the BC education system where it is the theory-du-jour.

Q2: What is the basis for such agreement? Why do people in the discipline accept it? What (if any) is the evidence for it?

I’ve posed a variant of these questions on twitter to Social Studies teachers in general, and to two "experts" in this field: Dr. Lindsay Gibson in particular, who is a professor of Social Studies Education at UBC, a student of Peter Seixas and deeply involved in the development and suffusion of the Concepts, and was on the curriculum writing team for BC Social Studies, and to Dale Martelli, a well-known secondary teacher of Social Studies and Philosophy, the president of the BC Social Studies Teacher's Association, and also a member of the same curriculum writing team. I asked: “Assuming that the Historical Thinking Concepts are generally accepted as a basis for sound practice in Social Studies classrooms, a) What is the basis or evidence for such agreement? b) Why do people in the discipline accept it?” I’ve also posed these questions to executive members of the BC Social Studies Teachers’ Association. My assumption, of course, is not a certain one but is so close to my intended area of research that I’d be remiss not to start there.

While awaiting responses, I’ll make some predictions.

Basis for agreement:

- the HTC/GTC have gained general acceptance as guiding concepts in Social Studies education because they are embedded in our revised curriculum and have been promoted widely as part of the curriculum implementation process

- the HTC/GTC fill a gap in traditional practice where the skills, mindsets, and disciplinary thinking associated with Social Studies did not have a single over-arching purpose or organization schema. The HTC propose to develop the ability among students to “think like a historian” (and the GTC to “think like a geographer).

Basis for acceptance:

- the concepts were picked as the basis for the competency-based curriculum because the Ministry needed a framework and the HTC cam ready-made and supported by influential members of both the academic historical community and history education community in Canada, largely (but not solely) through the work of the Historical Thinking Project

- the concepts were already familiar to many Social Studies teachers and there is a growing body of literature and teaching resources to support their use in K-12 Education. Sometime the practice follows the principles, sometimes the practice follows the resources. In this case, they came packaged together

- compatibility of the HTC/GTC with numerous accepted parallel or integrated approaches to Social Studies including skills-based, content-based, thematic vs chronological (historical) or sequential (geographical) course designs, active citizenship, focus on Indigenous reconciliation, “maker” and inquiry-based programs, identity work, and place-based/land-based/place-responsive education

Evidence for suitability of principle, law, or concept:

- respect for level and longevity of research, theory-making, practice, and output (e.g. learning resources) from Seixas et al for the HTC and Case et al for the GTC

- the theories behind the HTC (and to some extent the GTC) are influenced by and compatible with Contructivist Theory, which has dominate education off and on for decades, and Inquiry-Based Learning, which is another direction supported by the revised BC curriculum

- use by Ministry of Education and uptake by BC teachers -- maybe some circular reasoning here: faced with many choices, the Ministry picks a great framework; the framework is great because the Ministry picked it from among all the alternatives

Update (Sep 7): I didn't get a whole lot of uptake on the twitter end of things, but targeting Dale Martelli and Lindsay Gibson proved to be fruitful. Dale Martelli, The BC Social Studies Teachers' Association president, replied with a detailed challenge to the question (wonderful) and provided me with a list or recommended reading that positioned other "portal concepts" and ways-of-knowing as important for History/Social Studies educators and challenged the universal applicability of Historical Thinking Concepts. In his personal correspondence with me (Sep 5, 2019), he made salient points about how this trend to associate Social studies with Historical Thinking has featured in educational debates for decades, and that his sense was that compartmentalization was never a common pursuit among practitioners. He wondered at the provincial table "why we are not looking at the whole thing from a deeper ontological lens." Predictably, this was met by giggles -- the curriculum process was not invested to solve academic debates within the discipline, it was there to provide something simple enough to be be used by all teachers and consistent with the competency-driven theme being written into all of the other course curriculums. Dale also made a case that our curriculum should not be so focused on skill development and should respond to more of a Building approach to education. As always, my conversations with Dale leave me with more questions than answers. That's a good thing, from my perspective. By the way, here are the articles that he recommended for me -- a nice start for my own research on this topic.

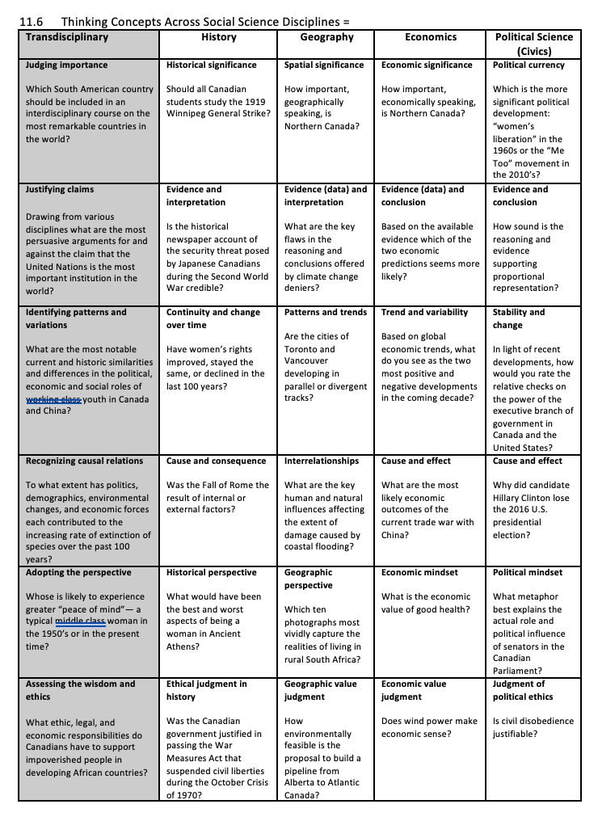

Lindsay Gibson, Assistant Professor of Curriculum & Pedagogy at UBC, also replied with a challenge to the question, that Historical Thinking was not necessarily seen as a basis of sound practice. Over the course of a series of related exchange, he share the following graphic that goes some way towards the view that Social Studies is more interdisciplinary that a simple reliance on Historical Thinking would suggest:

So, I now feel as if I asked the right question to determine whether my question was valid, and determined that it was not particularly valid! The answer appears to be that there is no solid basis for agreement on how Social Studies education should work, and that the many teachers are perhaps not very well informed about why the Historical Thinking Concepts were picked to headline the new Social Studies curriculum.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed