One of the things I like most about being a student is that coursework, specifically class time, provides a rare opportunity to think abstractly. So many of the tasks that fill my week are practical or purpose-driven in some way, but the interplay of ideas, dialogue, reading, and provocations that feature in a good class are like a spa visit for my brain. Of course, there are expected outcomes, assignments to complete, curriculum to absorb, and designated discussion topics of the day that command one's attention while in class, but the mind is a big enough place to wander around and outside of the syllabus, especially when the main expectation in a class setting is to think. One of my colleagues at D.P. Todd Secondary, where I worked from 2003-2018, used to place a note on his wall for students to see: "How have I invited you to think today?" This was both a powerful invitation for students to become engaged in class, but was also a significant commitment on the part of the teacher -- he was in fact holding himself accountable for facilitating lessons each day that engage minds. Unfortunately, there are many secondary classrooms where this is not the case. There might as well be the same sign in the wall in our NRES classroom, because here I have been invited to stretch my thinking, not just forward (i.e. consideration of new ideas of engagement with concepts from fields that are outside of my experience), but backwards -- the sense that everything I have learned in 50 years about the old, science, nature, ecology, education, society, geography, language, philosophy, etc., is being called upon to synthesize responses. A process most enjoyable. For the most recent class, my thinking went a little more whimsical, hence Mondrian's Law.

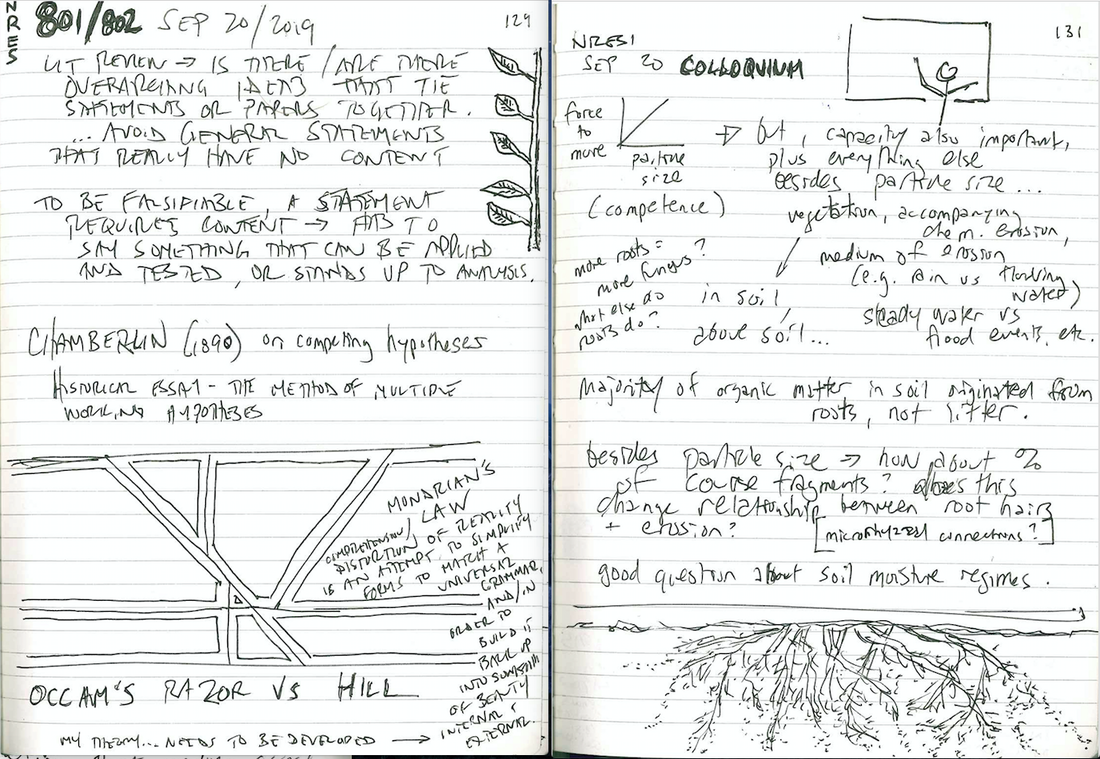

Mondrian's Law, an invention of mine as far as I can tell, is the result of my fixation on Simplicity from last week's class and readings, and perhaps a response to drawing some intersecting lines on paper or a consideration of the difference between Occam's Razor and Occam's Hill. Mondrian's Law is an attempt to set a scene for social science methodologies that embraces the abstract. Who's up for blurring the lines between theory and practice? This idea, from all appearances, is inchoate at best, barely set free from the barn. Piet Mondrian was a brilliant Dutch artist who developed an abstract style of painting that sought to access universal truths and yet remain in tension (or dialogue?) with reality. Here is a link to a good bio <Guggenheim on Mondrian>, and sense of the art that is most often connected with Mondrian <google search: piet mondrian art>. I associate Mondrian with trees and his wonderful geometric representations of them, and have often thought that if I ever took art more seriously (speaking of inchoate) I would start with Mondrian because I love trees and been enamoured with what he has done with them. The Law, as I imagine it, is about the comprehension and distortion of phenomena in an attempt to simplify forms such that they are resonate on the same frequency as universal grammar (c.f. Chomsky) or create what the architect Christopher Alexander popularized as "Pattern Language," and are then built back up into something of internal and external beauty that reflects a more poetic, and yes, a simpler explanation, than direct representations of phenomena. Basically, Mondrian's Law is about stripping down reality to basic elements as they are perceived by participants, and using those basic elements to recreate portrayals of reality that have a deeper connection for the participant than what they get from direct observation. I suppose this could be Picasso's Law as easily as Mondrian's. What;s that quote from Picasso? "We all know that art is not truth; art is a lie that makes us realize truth." I'm hoping this is sufficiently weird that it has not already been theorized by someone else. On the other hand, it is extremely common in art, from what I can gather, although it may be a newcomer on the social science scene. I'll need to sit down with a bona fide phenomenologist to find out for sure.

Mondrian's Law, an invention of mine as far as I can tell, is the result of my fixation on Simplicity from last week's class and readings, and perhaps a response to drawing some intersecting lines on paper or a consideration of the difference between Occam's Razor and Occam's Hill. Mondrian's Law is an attempt to set a scene for social science methodologies that embraces the abstract. Who's up for blurring the lines between theory and practice? This idea, from all appearances, is inchoate at best, barely set free from the barn. Piet Mondrian was a brilliant Dutch artist who developed an abstract style of painting that sought to access universal truths and yet remain in tension (or dialogue?) with reality. Here is a link to a good bio <Guggenheim on Mondrian>, and sense of the art that is most often connected with Mondrian <google search: piet mondrian art>. I associate Mondrian with trees and his wonderful geometric representations of them, and have often thought that if I ever took art more seriously (speaking of inchoate) I would start with Mondrian because I love trees and been enamoured with what he has done with them. The Law, as I imagine it, is about the comprehension and distortion of phenomena in an attempt to simplify forms such that they are resonate on the same frequency as universal grammar (c.f. Chomsky) or create what the architect Christopher Alexander popularized as "Pattern Language," and are then built back up into something of internal and external beauty that reflects a more poetic, and yes, a simpler explanation, than direct representations of phenomena. Basically, Mondrian's Law is about stripping down reality to basic elements as they are perceived by participants, and using those basic elements to recreate portrayals of reality that have a deeper connection for the participant than what they get from direct observation. I suppose this could be Picasso's Law as easily as Mondrian's. What;s that quote from Picasso? "We all know that art is not truth; art is a lie that makes us realize truth." I'm hoping this is sufficiently weird that it has not already been theorized by someone else. On the other hand, it is extremely common in art, from what I can gather, although it may be a newcomer on the social science scene. I'll need to sit down with a bona fide phenomenologist to find out for sure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed