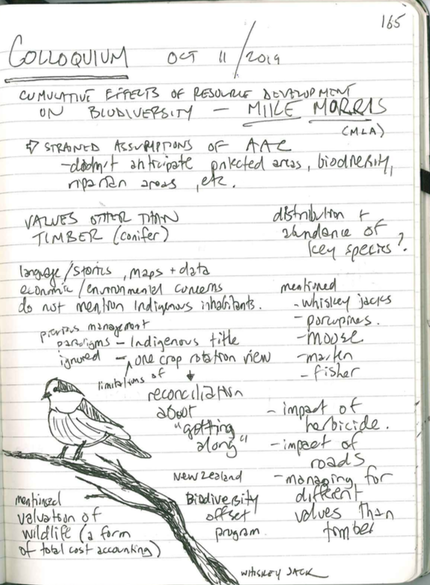

This presentation engendered a wide range of responses from the audience, some of which I could gather from open questions and comments, some of which I gleaned from conversations afterwards. These responses included a basic satisfaction that a politician was paying attention to these issues, an appreciation for the experience that Mike Morris brought to the topic, and revulsion that someone in a position of power and influence only seemed to come to the realization of the serious impact of resource development after his power and influence has waned. I think I can own the latter two of those sentiments, an appreciation for his decades of ecological observation in the region, and the bitter taste one gets when a politician talks about how they tried to get an issue on the radar of government but it just wasn't on the priority list. I was also concerned that Indigenous concerns (e.g. land title, resource decisions) seemed to be in afterthought in the presentation, that reconciliation was simply about "getting along." A key point Mike made was to talk about the strained assumptions of the Annual Allowable Cut (AAC). For too long it failed to anticipate protected areas, biodiversity, riparian areas, and so on.

My reference points for industrial forestry go back to my own time working in the woods in the 1980s and 1990s. During the four-month summers between years at university, a couple of longer 8-month stints, and as a transition to teaching, I tried my hand at many forestry jobs: cone-picker, herbicide applicator, research assistant, treeplanter, compassman, surveyor, and finally as an ecosystem geographer, a fancy way of saying that I dug soil pits and classified plants. The range of resource ethics I had to choose from back then were limited, essentially variations on exploitation vs conservation. Resource management has taken many turns since then, and with the recent passage in BC to support the implementation of UNDRIP, I don't think we can go back to the old resource ethics, exploitation vs conservation. There are layers of complexity to consider now.

My reference points for industrial forestry go back to my own time working in the woods in the 1980s and 1990s. During the four-month summers between years at university, a couple of longer 8-month stints, and as a transition to teaching, I tried my hand at many forestry jobs: cone-picker, herbicide applicator, research assistant, treeplanter, compassman, surveyor, and finally as an ecosystem geographer, a fancy way of saying that I dug soil pits and classified plants. The range of resource ethics I had to choose from back then were limited, essentially variations on exploitation vs conservation. Resource management has taken many turns since then, and with the recent passage in BC to support the implementation of UNDRIP, I don't think we can go back to the old resource ethics, exploitation vs conservation. There are layers of complexity to consider now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed